Today’s Perfect Quarterback Played a Quarter-Century Ago

By Michael Rosenberg

Mike Quick saw the offense of the future in training camp, and it made him think of the past. This was a few weeks before Chip Kelly’s Eagles obliterated Washington on the first Monday night of the season. Quick, an All-Pro wideout in Philadelphia from 1982 to ’90, saw the spread formations, read-option runs, wide receiver screens and well-designed downfield passing plays, all at a frenetic pace to keep the defense off balance. He turned to a former Philly teammate, Gary Cobb and said: “Imagine Randall in this offense.”

Says Quick: “It would have been unstoppable. Randall would have rewritten the record books in an offense like this.”

Randall is Randall Cunningham, and his biggest flaw, in retrospect, was being three decades ahead of his time. Cunningham played for the Eagles from 1985 to ’95. How good was he? Well, take the superlatives for Robert Griffin III, Colin Kaepernick, Michael Vick and Cam Newton, and apply them to Cunningham. Most fit. He was so big, fast, elusive, rangy and strong-armed that Hall of Famer Dan Fouts says: “There was nobody similar to Cunningham when he was at the top of his game. He was just a different cat.”

Put him in Kelly’s system, and “Randall would have been a first-ballot Hall of Famer,” Quick says. But when Cunningham played, Kelly’s system did not exist. The read-option did not exist.

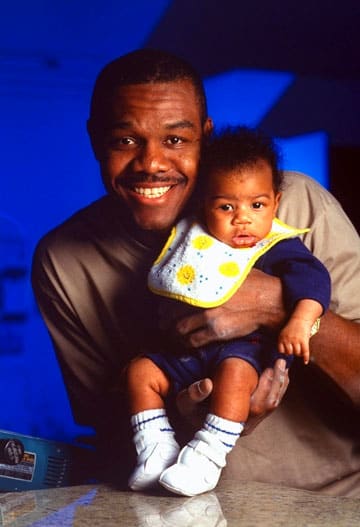

Look familiar? Randall Cunningham II—a.k.a. RC2—is a top dual-threat high school quarterback. (Tony Sanchez)

The future looked a lot different back then. Bill Walsh had revolutionized the game with his West Coast offense, and that’s where the NFL seemed headed: offenses built around short quarterback drops and quick passes, and making sure the quarterback released the ball before he got hit. From high school to early in his NFL career, Cunningham—one of the great running quarterbacks of all time—was coached not to run.

“Yeah, it would be great to play nowadays,” says Cunningham. “But you know ... I’m 50 years old.”

What would Randall Cunningham have done in this era? We’ll never know.

Or maybe we will. Maybe the answer was on TV recently, when Bishop Gorman High in Las Vegas played its opening game of the season. Bishop Gorman’s senior quarterback is a potential Olympic high jumper and one of the nation’s top dual-threat quarterback prospects. He has only been a starter for a short while, because the school had another top prospect last year. Yet Louisiana State, Baylor and a dozen or so other colleges have offered him scholarships, and more will surely follow.

The kid’s name is Randall Cunningham II.

“You look at him, you’re like, ‘Dang, he’s Randall running the offense,’ ” says former Eagles receiver Calvin Williams, who watched Bishop Gorman’s game on TV. “If you wonder what Randall could have done, just take a look at this kid for the next three or four years.”

* * *

Three facts help tell the story of Randall Cunningham Sr.

• He once led the NFL in passer rating (106.0 in 1998).

• He once punted the ball 91 yards in a game (against the Giants in 1989).

• He once finished in the top 10 in the league in rushing (942 yards in 1990).

“When I look at it now, they give me credit for being a great athlete,” Cunningham says. “You can’t just put a quarterback in the category of being a great athlete. There has to be some kind of credit, to say: This guy was not a normal guy.”

Normal? Go do a YouTube search for “Randall Cunningham to Fred Barnett.” You’ll see Cunningham on 3rd-and-14 from his own 5-yard line, with the pocket collapsing, run right and somehow avoid getting swallowed by Bills defensive end Bruce Smith, like a fish jumping out of a shark’s mouth. Then you’ll see him run left, pivot and chuck the ball 60 yards into the Buffalo wind. Barnett catches it and runs the rest of the way for a 95-yard touchdown.

Fouts was calling the game for CBS with Verne Lundquist. On air, he said the play “just defies description: Cunningham knows he is in trouble in the pocket. He knew that Bruce Smith was coming. And he makes a play that only he can make.”

Then there was the time Giants linebacker Carl Banks turned Cunningham horizontal. It should have been a sack. But Cunningham managed to land on one foot and one hand while still holding the ball, and—“like a cat,” Quick says—bounced to his feet. Then he immediately fired a touchdown pass.

He did stuff like that all the time. Former Eagles tight end Keith Jackson says of the play against the Giants: “It happened repeatedly in practice.” And as Fouts points out: “The rules in those days, the guys coming after him, they could do whatever they want.”

Former Eagles wideout Mike Quick says 'Randall would have been a first-ballot Hall of Famer' had he been able to play in Chip Kelly's high-octane offense.

Cunningham says the 91-yard punt was a fluke—the wind was so extreme that day that the ball moved off course between leaving his hands and hitting his foot. “I shanked it,” he says, but for some reason the ball started spiraling. The wind did the rest. If Giants kick returner Dave Meggett had not picked it up, Cunningham says, “I’m telling you right now, that ball would probably be in Russia somewhere.”

Maybe it was the wind. But Cunningham also had an 80-yard punt once, and he was an All-America punter at UNLV. (He punted only rarely in the pros.) Quick says, “There were so many times when he would do things [in practice] and you would look around at other people with your mouth dropped and they had the same reaction, like: What did I just see?”

That question dogged Cunningham for much of his time in Philadelphia. What did I just see? Obviously, he was a star. But was he simply an athletic freak or truly a great quarterback? What did you see?

The SI cover from Sept. 11, 1989.

Cunningham was heavily praised. Sports Illustrated put him on the cover with the billing THE ULTIMATE WEAPON. He made four Pro Bowls and twice won the Bert Bell Award as the pro football player of the year. But he also took more grief than the other elite quarterbacks of his era.

There were a lot of factors at play, and even now it’s hard to distinguish among them. He played in Philly, where the first word most babies learn is “boo.” He was a black quarterback in an era when there weren’t many others.

At times Cunningham was his own worst P.R. man. He wore gold-tipped shoelaces. Quick remembers him riding around blue-collar Philly in a limousine, and wearing the same kind of jacket Michael Jackson wore in a video. When critics questioned him, he wore a hat with the words “Let Me Be Me” on it.

When the Eagles lost in the playoffs, fans and some in the media conflated Cunningham’s playing style with his personal style. They wondered if he was too interested in being flashy to win a Super Bowl.

In 1990, he threw 30 touchdown passes (second in the NFL), had a 91.6 passer rating (fifth), threw for 3,466 yards (sixth) and ran for 942 yards (ninth) on just 118 carries—an average of 8.0 yards per rush. But it all seemed like costume jewelry when the Eagles scored six points in their playoff loss to Washington. Much of the blame fell on Cunningham. People said he wasn’t a winner, but when he retired, his record as a starting quarterback was 82-52-1.

He was never the most refined quarterback. Quick says Cunningham worked hard but could have used “better tutelage—when you’re as talented as Randall was, he probably didn’t get all the small teaching points because he could already outplay everybody. At some point that catches up to you.”

It did not help that Cunningham spent his prime years playing for two coaches who, for different reasons, were not the best fit for him. Buddy Ryan was a defensive wizard who didn’t spend much time worrying about his offense; he routinely told his players that if Cunningham just made four or five big plays, the defense would take care of the rest. When Ryan was fired after the 1990 season, he was replaced by his offensive coordinator, Rich Kotite, who (as any Eagles fan can tell you) was not Bill Walsh.

Long before NFL coaches, Cunningham realized that the best way to use a great athlete is to give him space. ‘I was asking people to do that way back in the day,’ he says. ‘Let’s open the offense up.’

But when Cunningham says, “Many people didn’t understand how to groom me,” it is also a commentary on the era. Cunningham says he once ran a 4.29 40-yard dash on a rubber track, but “in high school they did not let me run [the ball].” He was a quarterback. At UNLV he ran some more, but since sacks counted against rushing yardage, it didn’t show up in the stats.

Jackson, a four-time Pro Bowler, says: “People would argue: Is he a prototypical quarterback? No. But if you ask the question today, people would say: Kaepernick who? Russell Wilson who?”

The Eagles drafted Cunningham in the second round as a drop-back quarterback, the only kind that really existed in the league. At one point Philly had only three running plays for him: a conventional QB sneak for when they needed a yard, and RC Left and RC Right.

“I actually informed some of the coaches: I don’t need these designed plays for me to run,” Cunningham says. “It seemed like every time the play was designed for me to run, it didn’t work. It was choreographed.”

Cunningham ran for almost all of his yardage after plays broke down. He also threw exceptionally well on the run. He recognized, long before many NFL coaches did, that the best way to use a great athlete is to give him space.

“I did not want one receiver out wide, two tight ends and two running backs,” Cunningham says. “I said, ‘Let’s open up the formation, split wide receivers and running backs out. It’s kind of amazing, because that’s what they are doing nowadays. I was asking people to do that way back in the day. If you want me to run, let’s open the offense up.”

* * *

Today’s Perfect Quarterback Played a Quarter-Century Ago

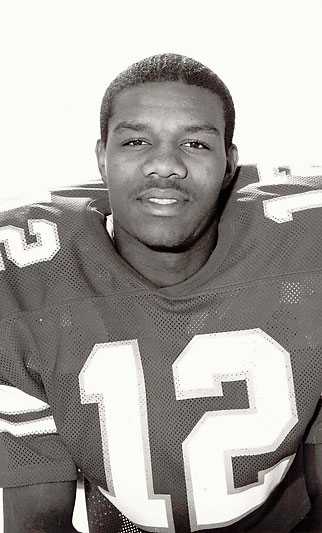

As a Runnin’ Rebel, a nickname that fit Cunningham’s style. (UNLV/Collegiate Images/Getty Images)

Philly tapped Cunningham out of UNLV in the second round in ’85, but the Eagles but had to wait for the USFL to fold before they were sure they’d get him. (Peter Read Miller/SI)

In action against the Raiders at the L.A. Coliseum in November 1986, after he had replaced the injured Ron Jaworski as Philly’s starter. (Andy Hayt/SI)

Cunningham rushed for 4,928 yards in his career, second among quarterbacks only to Michael Vick. (Mitchell Layton/SI)

His athleticism kept plays alive after the protection broke down. (

Cunningham’s mechanics weren’t ideal, largely because he wasn’t coached. Buddy Ryan routinely told players that if Cunningham just made four or five big plays, the defense would take care of the rest. (Lou Capozzola/SI)

The Fall Guy: Randall took heat from fans for Philly’s postseason futility—the Eagles were 1-4 in the playoffs under him, including a January 1991 loss to Washington. (Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated)

Five times in his career Cunningham led the league in sacks. He was taken down 484 for times for a loss of 3,537 yards over his 16 seasons. (Jeffrey Phelps/SI)

Randall had flair off the field but was all business on it. (Jeffrey Phelps/SI)

Reggie White gave chase in a 20-17 Eagles win in September ’93. Philly won its first four that year, but Cunningham went down for the season in the fourth game season and the Eagles finished 8-8. (Jeffrey Phelps/SI)

On the run against the Cowboys in 1994—watch out for that pitching mound! (John Biever/SI)

Speaking with reporters after his last game at the Vet as an Eagle, a December ’95 playoff win over Detroit in which he played sparingly. (Al Tielemans/SI)

After sitting out a season, Cunningham found new life in Minnesota in ’97 and earned his only All-Pro nod the following year. (Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated)

Cunningham’s scrambling days were mostly over by ’98; he carried 32 times for 132 yards that year. (Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated)

But the arm was alive as ever—throwing to Randy Moss and Cris Carter, Cunningham had a career-best 34 TD passes and a 106.0 rating. (Bob Rosato/SI)

Cunningham with Brian Billick, offensive coordinator of the Vikings in ’98. Minnesota scored 556 points that season, at the time an NFL record. (Bob Rosato/SI)

Cunningham joined the Cowboys as Troy Aikman’s backup in 2000 and saw action in three games. (Donna McWilliam/AP)

A Raven, then nevermore: Randall won both his starts as Elvis Grbac’s backup in Baltimore in ’02, his final NFL season. (Fred Vuich/SI)

Randall returned to UNLV and received his diploma in 2004. (Joe Cavaretta/AP)

A man ahead of his time. (John Biever/SI)

Cunningham retired after the 1995 season, when he was benched for Rodney Peete. He came out of retirement a year later to join the Vikings. He was not the most athletic quarterback in the league anymore, but Minnesota did what the Eagles hadn’t done: They put him behind an excellent offensive line and gave him great coaching.

In 1998, with Pro Bowlers Randy Moss, Cris Carter, and Robert Smith in his huddle, and offensive coordinator Brian Billick coaching him, Cunningham put together a Brett Favre-like late-career season with Minnesota: 106.0 passer rating, 34 touchdown passes, 10 interceptions, 8.7 yards per attempt. Cunningham was first-team All-Pro, and the Vikings scored 556 points, at the time the the most ever by an NFL team. They came within a field goal of making the Super Bowl.

It was Cunningham’s last hurrah. He got off to a rocky start in ’99 and was replaced by Jeff George. After backup stints with the Cowboys in 2000 and Ravens in 2001, he retired, moving to Las Vegas to found Remnant Ministries, where he is the pastor.

Taller and faster than his dad was in high school, Randall II has another advantage: He was born at the right time.

On the afternoon of Monday, Sept. 9, Cunningham watched his son—tall and rangy like his father at 6-5, 185 pounds—practice with Bishop Gorman. The younger Cunningham used to feel pressure to be like his famous dad, but he says that has passed.

“He tells me, ‘Don’t try to be like me,’ ” Randall II says. “ ‘Be better than me.’ ”

Randall Cunningham Sr. with his son, Randall Cunningham II, in March 1996. In addition to being a top QB prospect, RC2 is an elite high jumper.

Better? How? Fouts says of the elder Cunningham: “As a runner, he reminds me a little bit of Kaepernick.” Quick says of the league’s young quarterbacks: “He could do more than most of these guys. I would compare him to the guy in San Francisco, but physically, he had more than that kid. And I think Kaepernick is extremely gifted. Randall could shake people, and if you tried to go low on him he would jump over people. He was like the plastic man the way he would keep his balance.”

It is hard for any quarterback to be better than Cunningham was. Yet he points out his son is taller and faster than he was in high school. Randall II’s best high jump in competition of 7 feet, 3 1/4 inches was the highest jump in the country last year, according to track site dyestat.com. Randall II does not throw quite as hard as his father did yet, but he understands the game better, because he has a pretty good teacher.

“His knowledge of the game is beyond what people realize,” Randall Sr. says. “He understands pass protections in the NFL because I taught him all that. Schemes, down and distance ... I didn’t understand any of that. I learned it in the college and the pros.

Randall II has another advantage: He was born at the right time. He says Bishop Gorman has run the read-option on roughly a quarter of its plays this year. He also says, “I feel like I’m able to drop back and pass, and if I need to, I can continue the play if I have to.” When Baylor offered him a scholarship to play RG3’s position there, the coaches started calling him RC2.

After watching his son’s practice, Randall Cunningham went to one daughter’s volleyball practice and another’s ballet practice, both with his 1 1/2-year-old daughter with him. So he did not get to watch the Eagles’ Monday Night season-opener. But Randall II got home in time to watch some of Chip Kelly’s debut.