‘Father Time Ain’t On My Side, That’s the Truth’

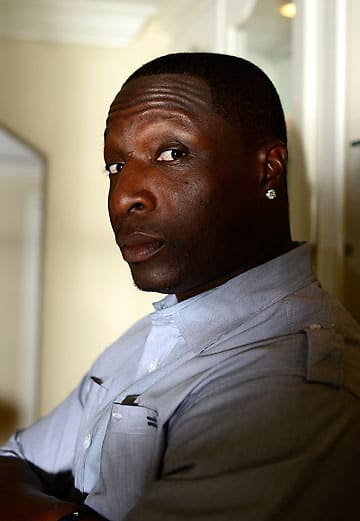

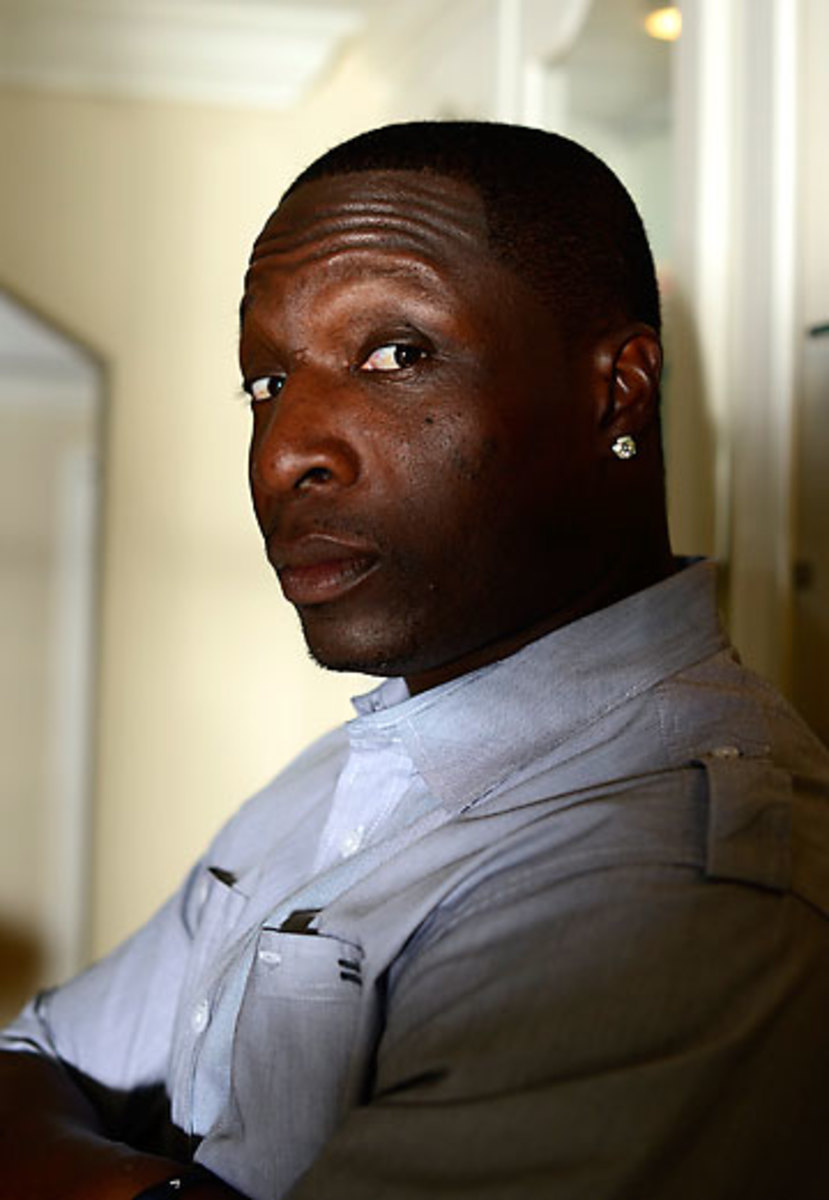

Fred McCrary in the quiet room he retreats to when the headaches get bad. (Pouya Dianat for Sports Illustrated)

CANTON, Ga. — The sand-colored, brick-front home with the pointed roof and the rock-lined driveway sits at the top of a hill. Reaching it requires a drive through modern-day Mayberry, where trees line meandering streets and laughter from playing kids can be heard during Saturday morning strolls. Peer across the street from its perch and you can see slivers of a golf course that’s as easy on the eyes as it is tough on the nerves.

Can football change? Will the sport become safer? How are concussions impacting the game’s future?

Introducing an in-depth series where we tackle those questions, starting at high schools and continuing into college and the NFL. Read the entire series.

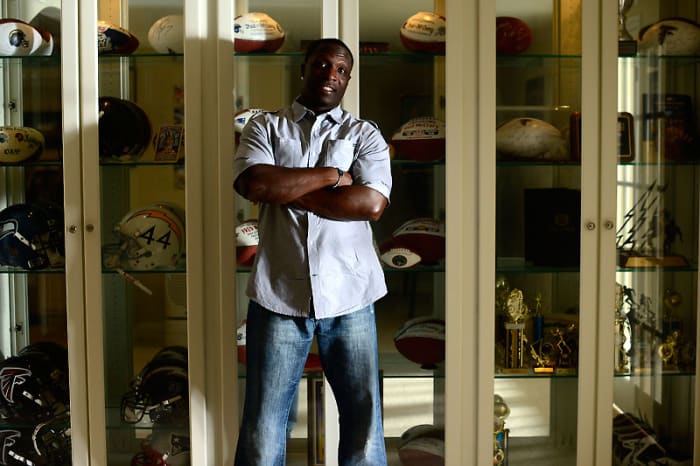

The 6,000-square foot, five-bedroom, five-bath home is where Fred McCrary lives with two of his three sons, ages 11, 10 and 7. It’s one of the trophies he earned from an 11-year NFL career that ended 2007. The 41-year-old played fullback for Philadelphia, New Orleans, San Diego, New England, Atlanta and Seattle, starting 65 of 128 games and blocking for Ricky Watters, Charlie Garner, Warrick Dunn and LaDainian Tomlinson, among others. His basement is a shrine to those years. A wall-length trophy case features helmets of the Falcons, Patriots, Chargers and Seahawks, as well as game balls, framed jerseys and a key to the city from his hometown of Naples, Fla.

Still, the most prominent reminder of his playing days is a large, empty room that’s fronted by glass-paned double doors. This is where McCrary sometimes disappears for two or three days at a time to fight off migraines he attributes to the “hundreds” of concussions he sustained while playing football. When they attack the back of his head, with the acuteness of sharpened knives and the pressure of a closing vise, he pulls a couple of large, thick folded blankets from a closet and places them over the glass doors. He needs darkness and silence to make them disappear. The episodes occurred so regularly early in his retirement that his kids stopped knocking on the doors to ask what’s wrong. They knew daddy was having an attack, which meant they shouldn’t disturb him unless absolutely necessary.

Back then, the migraines would hit three or four times a month. Today they visit him once or twice a month, in part because he has learned to avoid the stresses that can trigger them. Nevertheless, McCrary remains scared. For himself. For his sons.

* * *

Fred McCrary’s cracked helmet from his training-camp collision with teammate Junior Seau. (Jim Trotter/SI)

The year is 2001, and the thrill of starting a new season has worn off for the Chargers. They’re a week-plus into training camp when the coaches notice the players are dragging, lethargic, in a fog thicker than the marine layer that hovers over the coastline just a mile or so from their UC-San Diego training site. Something has to be done, so the staff calls for a full-contact run drill to liven up things.

When the play is called in the huddle, McCrary feels a sense of anxiousness. It calls for him to take on perennial Pro Bowl linebacker Junior Seau in the “A” gap. To that point Seau had been having his way with the offense. He knew the schemes so well that he sometimes correctly called out plays at the line of scrimmage, just because the offensive formation. McCrary was entering his third season with the team, but he knew his job wasn’t safe. Few were. San Diego was coming off a 1-15 season in which it had lost its first 11 games. How could anyone other than stars such as Seau or safety Rodney Harrison or defensive tackle John Parrella be safe, particularly with new general manager John Butler watching so intently?

When the play call came in, McCrary tightened his chin strap and told himself to get low. He would need to get beneath Seau’s shoulder pads to win the battle. At the snap of the ball, Seau came charging through the gap, where McCrary was there to meet him. This time McCrary won, putting Seau on his back. But that’s not what got everyone’s attention. It was the force of the collision, so loud it could be heard a couple of football fields away. So violent that it left a 3-inch crack across the bridge of McCrary’s helmet.

“I’ve never seen anything like that before in my life,” McCrary said after practice. “I’m going to take [the helmet] home and get Junior to sign it, and I’m going to sign it, and I’m going to put it in my trophy case. That’s a piece of art right there.”

McCrary may have considered the helmet a badge of honor at the time—he still does today, featuring it prominently in his trophy case—but he soon realized the damage from the collision extended far beyond his equipment. When he saw spots and flashes of white after the initial hit, he dismissed it as a “ding.” But as the day progressed, his head began to hurt, and his equilibrium was off. When he saw Seau that night he complained that something was wrong. Seau responded by saying his own head was “on fire.” But the two kept their conditions a secret for fear they would be held out of practice.

When we played, you weren’t allowed to get hurt. You’ve fought all your life to become an NFL player. You don’t want that taken away from you, so you suck it up.

McCrary thought the symptoms would subside, but they wound up persisting for more than six months. On one occasion he lay in the bed at 2 in the morning, arms outstretched, clutching the edge of the mattress. His then-wife was so scared she pleaded with him to go to the emergency room. He refused because he feared it would cost him his job.

“My wife was like, ‘What’s wrong with you?! What’s wrong?’ ” McCrary recalls. “I knew what it was, but I didn’t really know, if you know what I mean. I can’t tell you how many face masks I broke from just running into linebackers. They’re five yards back, we’re five yards back and ... POW!!! Over and over. It has no choice but to take a toll on your brain. Me being an idiot, loving it, I kept doing it. But I didn’t really know the damage I was doing.”

He received an answer earlier this month when he watched “League of Denial,” the PBS documentary based on the book of the same name, which outlined the link between head trauma in football and long-term brain damage and how the NFL hid those dangers from players.

“You have a ray of emotions,” he says after viewing it. “You become angry, you become sad, you become hurt because they should have warned us. They should have told us about that stuff. They never did. Not any team that I’ve ever been on told me. It makes you angry, almost like they’re using us. It hurts.

“When we played, you weren’t allowed to get hurt. It was like, ‘He’s fine. Get him back in there.’ What are you going to do? You’ve got to feed your family. You’ve fought all your life to become an NFL player. You don’t want that taken away from you, so you suck it up. But if I had known the dangers, it absolutely would have changed things. I would have blocked differently. I wouldn’t have been going in there head-first as much. I would have been using my shoulders a lot more. I probably would have cut-block more instead of running in there hitting them face first. That takes a toll.”

‘Father Time Ain’t On My Side, That’s the Truth’

Over 11 seasons in the NFL, Fred McCrary had surgeries on his ankle, shoulder and knee and broke five bones, plus his nose multiple times. He says he had “hundreds” of what would be characterized as concussions today, and he’s feeling the effects. (Streeter Lecka/Getty Images)

Before they knocked heads in practice as Chargers teammates, McCrary and Junior Seau met up during McCrary’s rookie season with the Eagles in 1995. (Doug Pensinger/Getty Images)

LaDainian Tomlinson was one of the many tailbacks who were grateful to have McCrary clearing a path for them. (Stephen Dunn/Getty Images)

Avoiding contact was hardly McCrary’s style, though he seemed to do so as a Patriot on this play in a 2003 game. (Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustrated)

Atlanta was the fifth of six NFL teams for which McCrary played.

McCrary had just 25 rushing attempts in his entire career but was an effective pass-catcher out of the backfield. (Jesse Beals/Icon SMI)

Golf occupies much of McCrary's free time on the links; here he shares a laugh with Bo Jackson during practice for the Chik-fil-a Bowl Challenge last April. (Paul Abell/CFA-pr)

The mementos of his career are displayed with pride, but McCrary wonders where he will be physically and mentally a decade or two down the road. (Pouya Dianat for Sports Illustrated)

It’s an absolutely stunning autumn morning outside Atlanta. There is bright sunshine and low humidity. It reminds McCrary of his time in San Diego. He is up before 7 to get ready for his kids’ youth football games. Savion, 11, plays at 9 that morning, and Tyson, 7, plays 90 minutes later a short distance away. Middle son Jackson, 10, does not have a game on this day.

The McCrary boys are good players. Really good players. In the first game, Savion, a cornerback and running back, intercepts a pass, then takes a screen 60 yards for a touchdown. He opens the second half by returning the kickoff to the 1-yard line, something his father playfully barks at him about before leaving for Tyson’s game.

McCrary is the offensive play-caller for Tyson’s team, and on the first snap from scrimmage Tyson, a speedy quarterback, carries the ball around left end for a 30-yard touchdown. He has a handful of other dazzling runs, but his squad suffers its only loss in five games after losing a fumble and failing to recover two kickoffs in the third quarter, each of which led to touchdowns.

I would rather my sons play golf, basketball, soccer—anything other than football. But they love it. They want to be like me.

Watching the game is like witnessing the power of sport. It brings together communities. Parents, family members and friends fill the metal stands and line the chain-link fence. It doesn’t hurt that the cute quotient is off the charts—some kids appear to weigh less than their helmets. Still, the question of why McCrary would allow his kids to play a game so inherently violent and dangerous hangs in the air, considering what he now knows now.

“I allow my sons to play because this is what they want to do,” he says. “I give them choices. I would rather for them to play golf, I would rather for them to play basketball, I would rather for them to play soccer—anything other than football. But they love it. That’s what their dad did, and I’m their hero. That’s who they look up to. They want to be like me. So if they want to play football, I try to take preventative measures to help them out. In practice I make them wear a guardian cap [extra shell over the crown of the helmet] that helps reduce the risk of them getting concussions in practice. I try to school them on what a concussion is and to let me know if they ever have those symptoms.”

As a former player, McCrary believes he can spot the symptoms quicker than others. He says his sons’ leagues require that if a child sustains a concussion, a doctor and the kid’s parents must sign a release before he can play again. His sons have yet to sustain a concussion, he says, but he’s always on the lookout. If any of them sustained three in a year, he says he would prohibit them from ever playing again.

“It’s something that they want to do, so I let them,” he says. “I’m not going to shoot their dream down. Their dream is to play college football, high school, pro—who am I to shoot them down? That’s something they love.”

* * *

Fred McCrary at his home in Canton, Ga. (Pouya Dianat for Sports Illustrated)

McCrary, who was a plaintiff in the recently settled class-action lawsuit against the NFL, is back in his home, relaxing in his living room. Retirement was tough on him at first, but he has finally settled into a routine. He works out four or five times a week and watches his diet to keep in shape. He dabbles in real estate locally and in Florida with a friend, and is working toward becoming an NFL referee. On Friday nights in the fall you can find him officiating high school games, and he also works in the Arena Football League. His free time is spent on the golf course, where the left-hander has a swing that’s smooth and true. The previous Sunday he shot 74 on Echelon’s demanding 7,076-yard course.

Life is good, he says. He’s blessed. But he’s also scared about the future. He had surgery on his left ankle, right knee and left shoulder during his career. He broke five bones as well as his nose, multiple times. He has toes that don’t bend, fingers that barely bend, and in the next 10 years he believes he’ll need a hip replaced.

“Father Time ain’t on my side; that’s just the truth,” he says. “But I wouldn’t change anything but the concussions. All the hurts and pain, that’s part of the game. That’s what I signed up for. But them not telling me about my brain, that says a lot. That’s hurtful. That’s painful. That’s not fair. But what are you going to do?

“I’m pretty terrified, but I’m not going to quit living. I have kids to raise. I trust God. I’m a faith guy. If it’s time for me to go, it’s time for me to go. It’s not too much you can do. But what I’m scared of are the long-term effects [from playing]—my children having to take care of me, maybe having to put a diaper on me. That scares me half to death. I’m their hero; they look up to me. I know they would take care of me, but that scares me half to death that maybe one day I don’t know their names, or somebody helping me out of bed, helping me up the stairs. It’s scary. But I’m not going to fear it. I’m going to face it head on. What else can you do?”