Jermichael Finley Is Fighting Back

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — There’s a question on Jermichael Finley’s mind. No, not the one you’re thinking.

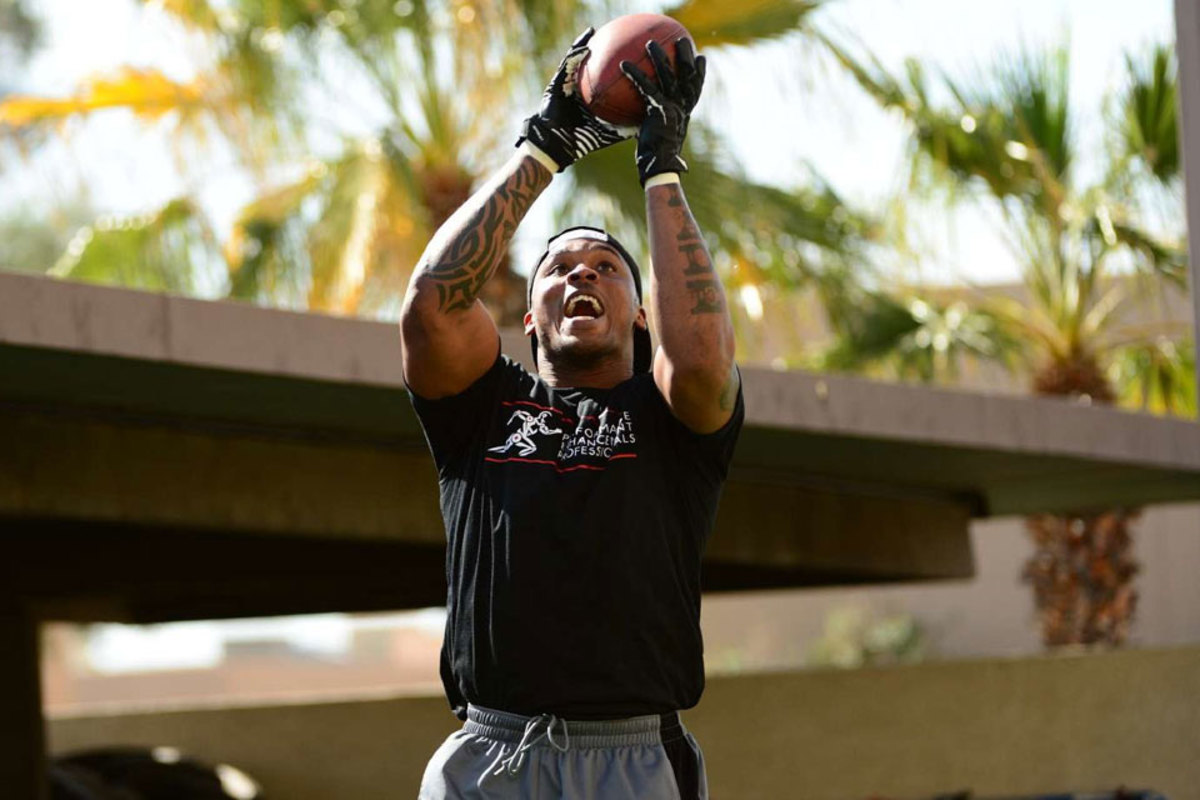

On an 81-degree afternoon in the desert, Finley is asking himself, “How can I make catching as hard as possible?”

This sounds a bit absurd. Four months ago the Packers tight end lay motionless on Lambeau Field after a collision with a Browns safety. Three months ago he had the C3 and C4 vertebrae in his spine fused together. And now he’s trying to make a physical task more difficult?

Yes. And he does. He palms a football that has 18 pounds of extra weight dangling off it. He grips it until he can’t any longer, several very long seconds. Then he repeats with his opposite hand. His fingers are exhausted. Finley’s other tactic is to wear old, beat-up receiver gloves that have long since turned from grippy to slippery.

Now for those catches. Some days Finley will snag a quarterback who’s also here training at the Performance Enhancement Professionals facility—a hotspot for NFL players, tucked in an office park in the Valley of the Sun—to throw him passes on the 50-yard outdoor turf. Today he’s catching from the JUGS machine.

Each repetition begins with him mimicking the top of his route and whipping his body around. Then Finley extends his 6-5 frame in all directions to catch the flying footballs. Considering that, post-surgery, he’s had to retrain his neck muscles to sync up with his eyes just to track a ball, each catch should be a win. But Finley has different standards. Seventeen balls are launched his way before he misses one, and this is not good enough. He tilts his head up to the clear blue Arizona sky and grunts.

* * *

Finley lowered his head to absorb the hit from Cleveland’s Tashaun Gipson—something he says he won’t be doing anymore. (Brian Kersey/Getty Images)

This is the latest leg of Finley’s road back from the Oct. 20 collision with Cleveland’s Tashaun Gipson, which silenced a stadium and left him with a contusion, or bruise, on his spinal cord. A week later Finley wrote a first-person account for The MMQB relating the question that ran through his mind as he lay on the field after that hit: “Will I play football again?”

In Finley’s mind this is no longer a question. But in truth it’s up to the NFL—the Packers or any of the 31 other teams who would be interested in the soon-to-be free agent—to decide.

“Maybe [I should] take my X-rays to the combine now that I’m a free agent,” Finley says, referring to this week’s leaguewide scouting convention. “That’s me being real.”

Actually, he’s not technically a free agent until March 11, so he can only meet with the Packers until that date. A visit to Green Bay for a full physical with the team’s medical staff is expected, and he’d welcome a return to the Packers “if they embrace me like they have before.” But this shows how confident Finley is that tests will bear out what he now feels in his body: normalcy.

Under the eye of PEP’s Ian Danney, Finley is dead-lifting more that 400 pounds, in reps of three. (John Biever/The MMQB)

It doesn’t really sound believable until you watch him work. He’s dead-lifting 429 pounds, in reps of threes, and casually chatting in-between about his new juicing habit: spinach-apple-pineapple, that is. He has quick answers to all the questions a doctor might ask: Balance? Restored six weeks ago. Pain? None for the past month, in any part of his range of motion. He loves football, and he expects to embark on a seventh professional season at no greater risk than any other player.

The neurosurgeon who performed Finley’s surgery, Joseph Maroon, has told him there’s a 99.9 percent chance the fusion will fully heal. After his latest X-rays, taken late last week, Finley says he was told that point could be reached within four weeks—and then Maroon would be prepared to clear him for football activity.

But the 26-year-old Finley may face other hurdles in signing his next NFL contract. Clearance from Maroon, the team neurosurgeon for the Steelers, would be a strong vote of confidence. But it’s possible some teams, despite Finley’s powerful frame and basketball-player athleticism, may not want to take on the risk of putting him on the field. The fusion was considered a proactive measure to fortify his neck and guard against another similar episode, but for some clubs the fact that it has healed may not be the sole determining factor for clearance.

The Packers, whose medical staff is considered to be among the more conservative in the NFL, did not clear former safety Nick Collins after his cervical fusion healed. But another Packers safety, Sean Richardson, was cleared after having a different pair of vertebrae in the cervical spine fused. No injuries are exactly the same, and neither Collins’ nor Richardson’s experience has affected Finley’s outlook.

“I spend enough time trying to get healthy,” Finley says, “so I don’t have time to look at other people’s injuries.”

* * *

Jermichael Finley Is Fighting Back

Finley’s work with Danney at PEP includes pressing a large ball against a wall, to strengthen the neck. Curls with 35-pound dumbbells add to the rigor. (John Biever/The MMQB)

Finley’s doctors say the vertebrae are close to fully healed. (John Biever/The MMQB)

Turn around for the full 360-degree effect. (John Biever/The MMQB)

Elastic band work builds upper-body strength. (John Biever/The MMQB)

Hurdles—both over and under—aid in flexibility and balance. (John Biever/The MMQB)

Finley often snags an NFL passer to throw to him. On Tuesday it was a JUGS machine. (John Biever/The MMQB)

Finley says he’s ready, and has no fear in coming back. (John Biever/The MMQB)

Finley’s bald head is squished against a large green stability ball, pressed up against a wall painted with the words, “Make No Small Plans.”

His neck—that neck—must hold his head steady while Ian Danney, owner of PEP, pounds the ball more than 15 times. They repeat this four times with Finley facing the wall, and four times with his back to the wall, and then Finley holds the same pose while doing biceps curls with 35-pound free weights. His nostrils are flaring and the veins are popping out of his forehead, but he stops just once, when the sweat dripping off his head is causing the ball to slide around.

“Man, he had surgery?” says Steelers linebacker LaMarr Woodley, who’s also training here. “Sure don’t look like it.”

Finley’s only visible external wound is a faint scar on the front of his neck, a thin reddish line that doesn’t look much more than an inch long to the right of his Adam’s apple. This is the incision where Maroon entered to make a bridge between the two adjacent vertebrae in Finley’s neck, using a small metal implant and a graft from a bone bank. The procedure took just 90 minutes; since Maroon and his team had to move Finley’s voice box, he was hoarse for a few days afterward.

Fusion is the process of the graft slowly joining the vertebrae together, and even as this nears completion Finley is still very much a work in progress. The muscles in the neck form a sling of sorts, and exercises like the ones against the wall allow the sling to become strong enough to stabilize the head. His physical therapy four times a week includes soft-tissue work to release neck scar tissue, and neuromuscular re-education, an intimidating title for tasks like re-coordinating the eyes and the neck. He spends as many as six hours a day at PEP.

“The injury has humbled J-Mike,” Danney says. “And I think that’s something he kind of needed, to be honest.”

“You can’t go out and tiptoe around. It’s a game of guys getting bigger, faster and stronger every year. So I’ve got to match that.”

Finley admits his attitude toward the NFL used to be, I’m supposed to be here. Now, for the time being at least, his only commitment with an team is joining the Packers’ fan vacation in Mexico this week.

At the same time, he has a confidence about his return—that he’ll play with the same intensity as before the injury, and with none of the fear he felt in those uncertain moments on the stretcher, when he pleaded with the doctors to tell him he’d be able to move his arms again. (The only thing he won’t do, he vows, is to lower his head in anticipation of a hit to protect his knees, as he did on the play that ended his season).

“Once I start changing the way I play, I shouldn’t go back,” Finley says. “You can’t go out and tiptoe around. It’s a game of guys getting bigger, faster and stronger every year. So I’ve got to match that.”

Reaching high: Finley’s Scottsdale workouts go for six hours. The goal: to be back on the field for 2014. (John Biever/The MMQB)

He admits there are times now when his mind will shift to his healing neck while he reaches for a pass or lifts a weight. “You are human,” he says. But his competitive instincts take over, as after that 18th football from the JUGS machine bounces off his hands, and he makes sure not to drop another.

Or as when Woodley needles him about signing with Pittsburgh. Finley immediately thinks about the daily battles the two would have, perhaps in those full-contact training camp practices the Steelers love. “Yeah, we’d go at it every day!” he shouts back at Woodley.

“Hopefully . . . ” Finley starts to say, then he stops himself. “No. When I get that chance, I’m going to maximize it.”