Understanding the Fine Print of Free Agency

The business of football is football this time of the calendar. Well into our second week of the new league year, let's take a look at what we've learned via two distinct avenues: the money and the people.

THE MONEY

• Still too early to call the CBA winner. While many have asked me to weigh in on a common perception that the NFL “crushed” the NFLPA in the collective bargaining agreement negotiations, I have tried to reserve judgment until we get further into the 10-year deal. Similarly, while many have said this year’s free agency spending proves the CBA is evening out, I also remain cautious.

My view is this: If top free agents did not make gains over the past week—most teams are flush with cash and cap room—then NFL players would truly have a problem. These “sweet spot” players (the 25- to 27-year-olds coming out of their rookie contracts) must be the flag-bearers of improved player economics. The CBA has worked so far to squeeze players on the way into the NFL (with mandatory four-year contracts at fixed rates for all draftees) and on the way out (older veterans are being cut or forced to take pay cuts). Prime free agents better take advantage; it is their one shot with leverage.

• A billion? Not so fast. Although it’s technically correct to say more than $1 billion in new contracts have been handed out, it is misleading. In research I conducted on the 2012 free agent class, there were a total of 76 free agent contracts with a length of three or more years. Two years later, 39 of those players are no longer with the team. Due to the structure of those deals and the fictitious amounts in the later years of contracts, teams can execute contracts with players with no intention of keeping them past one or two years.

Aqib Talib (John Leyba/Getty Images)

With zero long-term contracts fully guaranteed, the amounts are just numbers on a page, injected into the public discourse by player agents. Upon agreement, agents contact their preferred media contacts, usually opting for a national name over local media for maximum effect, and depict the numbers as conspicuously as possible. Those reports will then be used for marketing and recruiting purposes. In negotiating contracts, agents would sometimes ask me, “Can I say it’s worth what it could be if he hits all the incentives?” If that helped close the deal, fine by me.

• The real money isn't guaranteed either. So, you say, “the real money” is the guaranteed amounts, reported to be more than $500 million spent this past week? Sorry to again rain on the players’ parade, but those numbers are also not what they appear to be.

A “full” guarantee pays the player in the event he is released for either skill (deemed not good enough) or injury (unable to play due to a previous injury). In recent years, teams have managed to avoid full guarantees past the first year of these deals. How? Stay with me here.

At the time of signing (now), many of these contracts have full guarantees for 2014—of little value because players signed for any decent amount are not going to be cut this year—and injury-only guarantees in 2015. The latter converts to a full (skill and injury) guarantee for 2015 if the player is on the roster at the start of the 2015 league year. Yes, the likelihood of a player being released after the first year of these contracts is minimal. The point is that however unlikely, teams can release the player after the first year with no remaining financial obligation. Many of the bigger contracts signed this past week, such as Aqib Talib’s with the Broncos, are structured this way. And that, my friends, is not a guaranteed contract past the first year. Thus, that $500 million in guarantees is more like $250 million (one Albert Pujols).

As the shopping season now subsides a week into free agency, these are good times for NFL owners: Forbes values 23 of the 32 franchises at more than $1 billion, record-level television contracts are kicking in and player costs, while sounding high for public consumption, are largely illusory beyond one or two contract years.

THE PEOPLE

• New Jersey tug-of-war. In talking with sources on all sides of the negotiations, the Jets and Giants engaged in an interesting turf battle for the services of Dominique Rodgers-Cromartie.

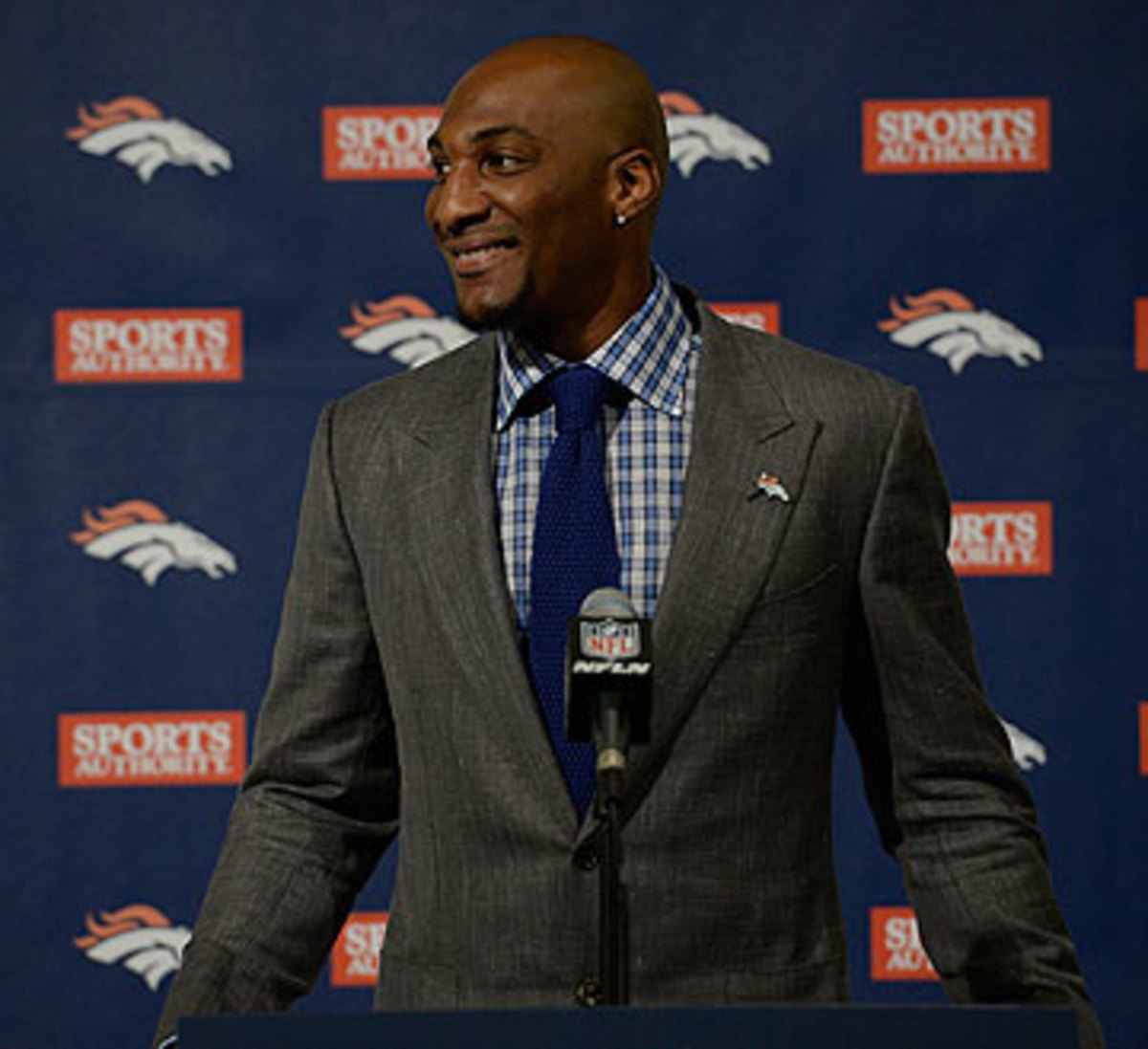

New Giant Dominique Rodgers-Cromartie (Justin Edmonds/Getty Images)

Rex Ryan excited Rodgers-Cromartie with a pitch to put the cornerback “on an island” and make him a star. The Giants offered him detailed plans for facing every team in the division, describing how they would use him against specific receivers on the Cowboys, Eagles and Redskins.

Thus, as it always does, it came down to economics. The Giants’ deal, with a $10 million signing bonus and $16 million over the first two years, was superior. The Jets held to the structure of a one-year $6 million deal, with options going forward, until it became clear the Giants were closing in. Only then did the Jets present a different type of structure, with general manager John Idzik scrambling to make up ground while attending Teddy Bridgewater’s pro day. By then, however, it was too late; the Giants had won the intra-stadium battle.

• Packers picked Peppers. As I know firsthand, the Packers’ signing of Julius Peppers—a one-year, $8.5 million commitment, with two non-guaranteed years tacked on—represents a dramatic departure from Ted Thompson’s “draft and develop” DNA. One can only wonder if this move was (Cheesehead) owner-driven.

The Peppers signing brings back memories of acquiring Charles Woodson in 2006, when he was still on the market a week into free agency. Although we were the only true suitor—I was the Packers vice president from 1999 to 2008—Woodson still required a month of recruiting, as there was reluctance to come to Green Bay.

When Woodson did arrive, there were some initial clashes with Mike McCarthy, as the culture was quite different than Oakland’s. Woodson eventually fit in and became a respected leader, even growing to enjoy living in Green Bay.

New Brown Ben Tate (Jeff Gross/Getty Images)

• Running on empty. Running back continues to be a low-value position, both in free agency and the draft. As a former agent, I feel for them. Fewer running backs are even receiving second contracts of any substance, let alone third ones. Players with limited mileage (Toby Gerhart, Donald Brown, Rashad Jennings, Ben Tate, etc.) have more market value than more accomplished backs such as Knowshon Moreno and Maurice Jones-Drew.

Does production early in a player’s career help market value or actually hurt it? The answer seems inverse to every other position.

• Saved from extinction. The Bengals’ decision to not match the Browns’ offer sheet to Andrew Hawkins illustrates a rare look into a facet of free agency that is nearly extinct.

Restricted free agents—three-year players with expiring contracts who can solicit offers subject to matching by their incumbent team—represent a dying breed. The rookie contract system implemented in the 2011 CBA requires every drafted player to sign a four-year contract, making any player worth keeping now ineligible to be a RFA. Now, only undrafted players (Victor Cruz, Hawkins) become RFAs.

The erosion of the RFA marketplace will continue and be pushed to near extinction by the new CBA. Hawkins might be remembered as the last RFA to receive an offer sheet.

• Agents play games too. Regarding the contract kerfuffle involving Emmanuel Sanders: well, it happens (through agent Steve Weinberg, Sanders reportedly committed to the Chiefs before signing with the Broncos). Free agency can be the Wild West; there are no ethics or etiquette. Agents and teams can have selective interpretations of statements, which often leads to hard feelings. Weinberg has been in and out the business for decades; this is certainly not the first time he has upset team management.

I remember one negotiation in Green Bay with a free agent with whom we agreed on a contract late one night. Overnight, another team pulled the player off a flight to Green Bay and he signed with them. We were livid and I promised the agent we would never do business with him again. However, a couple years later that agent had a player we liked. I had to swallow my pride and contact him; it’s all about the players. Nevertheless, reputations last and certain agents—and teams—are known as untrustworthy. It's all part of the business of football.