The Painkiller Problem

By Michael McCann

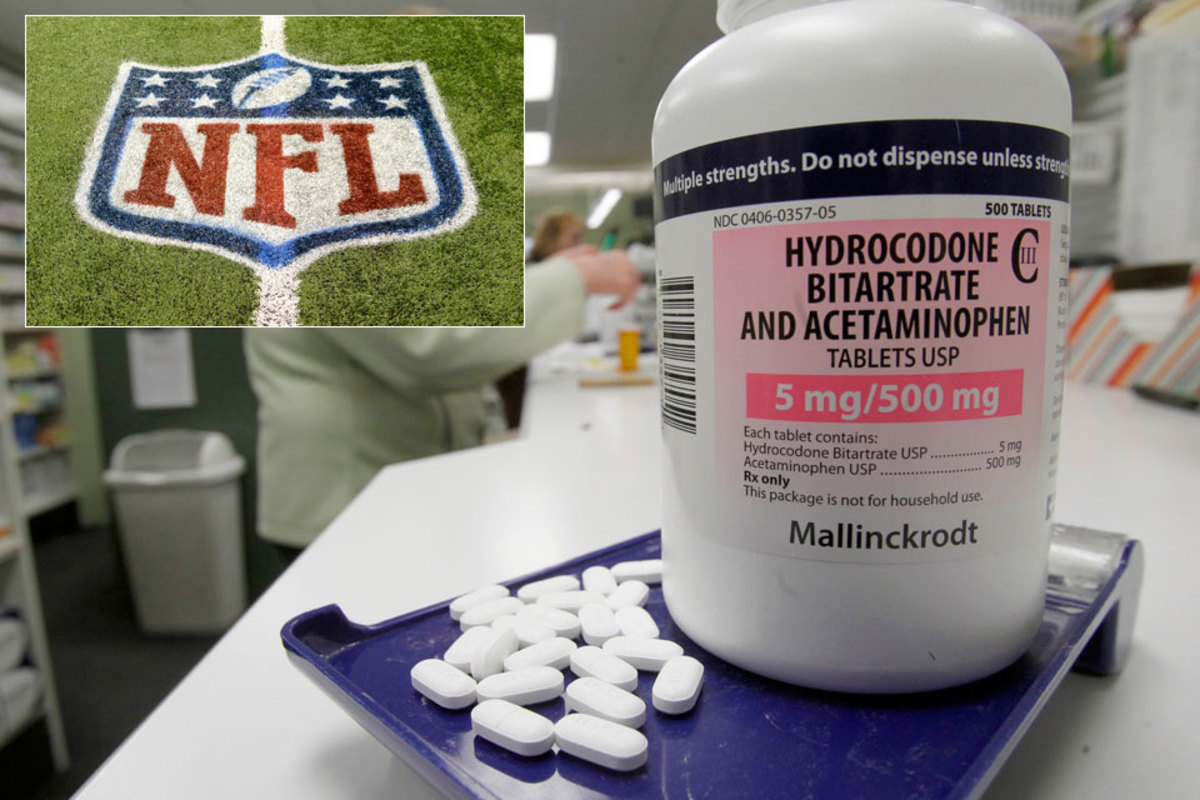

As the NFL tries to settle potentially billion-dollar litigation over the long-term neurological effects of concussions, the league has been hit with yet another major lawsuit: eight retired players, including Jim McMahon and Richard Dent, claim the league duped players into becoming addicted to painkillers. Attorneys for the players seek to transform the case into a class action on behalf of potentially thousands of other retired players.

The lawsuit portrays the NFL and its teams as taking extraordinarily unethical steps to suppress players’ pain so they could remain on the field. According to the complaint, team doctors and trainers routinely prescribed medications without prescriptions and without warning players about the risk of addiction and side effects. These allegations, if true, would constitute criminal acts under the federal Controlled Substances Act. Other allegations suggest team physicians and trainers regularly ignored players’ medical histories and disregarded the possibility of fatal interactions due to unique body chemistry.

Overall, the lawsuit depicts the NFL as a greedy enterprise which viewed players as disposable assets and treated them more like thoroughbreds than humans.

The painkiller litigation comes five months after U.S. District Judge Anita Brody rejected a proposed $765 million settlement between the NFL and retired players over concussions. Even if the NFL and retired players reach a new settlement over concussions and have it approved by Brody, some retired players likely would opt out of the settlement (as is their right) and file their own cases against the NFL. The NFL is likely to face player litigation for years to come.

NFL Legal Defenses

The league will answer the painkiller complaint in the coming weeks and ask that it be dismissed. As the litigation plays out, expect the league to offer at least six key defenses.

- Preemption

The NFL will argue that painkiller claims brought by the retired players are preempted by federal labor law. The league will insist that collective bargaining agreements between the NFL and NFLPA detail intricate rules for player health and internal grievance procedures for resolving questions about those rules. The NFL will assert that no court should hear a claim that players contractually assented must first be resolved through internal procedures.

The lawsuit depicts the NFL as a greedy enterprise which viewed players as disposable assets and treated them more like thoroughbreds than humans.

A preemption argument will be one of the NFL’s best defense tools. When unions and management agree to procedures to resolve disputes outside of the legal process, courts typically defer to those procedures. The NFL will stress that the league’s duty to players through team physicians and trainers is a matter of interpreting collective bargaining agreements, not applying torts and other areas of law.

To be sure, the NFL is not assured of victory by arguing preemption. The players have alleged fraudulent conduct by the NFL, and such conduct arguably is outside the scope of any collective bargaining agreement. Put another way, players and owners can’t agree to one side committing fraud on the other, and thus a fraud claim might fall beyond the reach of preemption.

Preemption is also a less certain defense for NFL activities that occurred between 1974 and 1977, and again between 1989 and 1993. During these years the league operated without a collective bargaining agreement. The NFLPA was also decertified between 1989 and 1993, meaning players did not negotiate policies with the NFL through a labor relationship. Although the NFL will stress that rules remained in place during periods without a collective bargaining agreement, watch for players to contend preemption does not apply during those periods.

- Blame the NFLPA

A related argument to preemption is that the players should place most of the legal blame on their union, not the NFL. Players entrusted the NFLPA with negotiating rules that impacted the diagnosis and treatment of their injuries, including rules for which painkillers could be used and under what circumstances painkillers could be prescribed. Along those lines, concern about NFL players overusing painkillers has been evident for years, without significant action by the NFL or—more importantly—the NFLPA.

As the exclusive bargaining unit for NFL players, the NFLPA has a duty of fair representation, which compels it to negotiate in good faith and competently. A credible argument could be made that, until recent years, the NFLPA prioritized financial compensation over safety in negotiations with the NFL. From the NFL’s vantage point, the health and safety of NFL players is a subject of collective bargaining, and the NFLPA has the primary responsibility to advocate on behalf of those players.

- Unreliable evidence and unavailable witnesses

The eight players involved in the lawsuit collectively played from 1969 to 2008. In some cases it might be difficult to corroborate their claims through team records, medical files, letters and memoranda. Documents transmitted on paper rather than through electronic correspondence might no longer be available. Without actual proof, allegations the league illegally dispensed painkillers might remain just that: allegations.

The fact that many of the allegations concern events occurring decades ago also invites questions about memory and recollection. Witnesses who attempt to recall events from decades back often struggle when cross-examined by lawyers, as those witnesses might easily confuse facts or fail to recall crucial details. Will retired players be so sure about their memories of playing days while under oath and subject to the penalty of perjury?

The plaintiffs must also contend with the unavailability of doctors and trainers implicated by the lawsuit. Many of those health care professionals likely have retired or passed away. It could prove challenging, and in some cases impossible, for players’ attorneys to depose individuals who are crucial to the case.

- Lack of causation and assumption of risk

J.D. Hill played seven seasons as a wide receiver for the Bills in the 1970s. (NFL Photos/AP)

A causal link between physical harm and painkillers might not be easily proven. Take allegations by J.D. Hill, one of the eight named plaintiffs. The complaint assigns blame on the NFL for Hill becoming addicted to painkillers, which eventually led to him suffering a weakened immune system, developing an abscess in his lung and becoming homeless. Hill’s account is genuinely tragic, but the NFL will likely argue that the league is not to blame. The league will first stress it acted reasonably. The league will also assert that even if it acted unreasonably, Hill’s harms are too attenuated from any wrongful conduct by the NFL. Other life events and personal choices, the NFL surely will contend, broke any causal nexus between the league and Hill.

The league is also poised to frame players as voluntarily using painkillers and thus providing consent. While the complaint argues NFL players—who unlike many other pro athletes play on non-guaranteed contracts— were aggressively pressured to play hurt, the NFL could reason that players ultimately made the decision to use painkillers. Along those lines, players could have at any point ended their NFL careers and pursued another line of employment. In their complaint, the plaintiffs anticipate this argument by asserting the NFL created and maintained a “culture of drug abuse.” The culture, the players contend, denied players a meaningful choice by denying them the necessary information to provide informed consent.

- Team doctors and trainers were independent contractors, not team employees

The employment status of NFL team physicians and trainers has varied over the years and by team, and has been a key issue in malpractice cases against team physicians. Some physicians and trainers have been employees of the team, while others have been independent contractors. Employers generally have higher legal exposure to the wrongful acts of employees than those of independent contractors. Watch for the NFL to argue that the league is less responsible for the actions of physicians and trainers who were independent contractors. Retired players, however, can respond by asserting that teams should not be able to delegate responsibilities of care to physicians and trainers merely through employment classification.

- Statute of limitations have expired

The NFL will argue that the retired players’ claims are barred by the relevant statutes of limitation. The statute of limitations is a legal device designed to ensure that claims be brought in a timely manner and before evidence and witnesses become unavailable. The players allege theories of negligence and fraud. These types of claims are generally available only for a handful of years following the negligent or fraudulent act. This might prove problematic for the eight named players, as most of their allegations concern events occurring prior to 2000, in some cases well before 2000.

In their complaint, the players recognize the NFL will cite the statute of limitations as a ground for dismissal. The players demand the statute of limitations be tolled (extended) on grounds the players were not warned and had no reason to know they were suffering harm by using painkillers.

Possibility of settlement

In the short-term, the NFL will deny the merits of the claim and try to convince a court to dismiss the lawsuit. But as NFL concussion litigation shows, the league may eventually conclude that settlement is a better strategy than litigation. The NFL is aware that fans, media and members of Congress are closely watching player safety lawsuits. There has been increasing concern in recent years that football is too dangerous and that outside intervention of some form may be warranted. Public perception is thus an important consideration for the NFL as it develops a legal strategy. Indeed, even though NFL attorneys believe lawsuits over player health are unlikely to prevail in court, those lawsuits could play out over years in a high-profile manner.

Recreational marijuana is legal in two NFL cities—Denver and Seattle—but the league prohibits its use for players, even for medical purposes. (Ed Andrieski/AP)

Consider some of the possible ramifications of lengthy and public litigations for the NFL. Pretrial discovery, which would involve players’ lawyers deposing league executives and team owners under oath and obtaining records from them, could unveil unflattering facts about the league and its owners. Pretrial discovery could also lead to NFL owners having to reveal closely-guarded financial information. Worse yet, should any of the player safety lawsuits go to trial, league officials would have to uncomfortably watch retired players and families tell jurors about the pain they’ve suffered. To avert these risks, the league might seek out a settlement with attorneys in the painkiller litigation, just as they have done in the concussion litigation.

An opening for marijuana?

The painkiller lawsuit raises serious questions about the health risks of painkillers commonly prescribed to NFL players. Both Robert Klemko (for The MMQB) and I (for SI.com) have written about the impact of marijuana legalization on the NFL. While the health benefits of marijuana remain a divisive topic, its gradual legalization raises the possibility that marijuana might eventually become a viable alternative to suppress pain. As one prominent NFL agent told me, “What is the alternative to marijuana? The alternative sucks. Think about what players take for pain—they take much more serious and much more addictive drugs. Vicodin. Percocet. Oxycodone. These are highly addictive and synthetically manufactured drugs. ... They can rip up your insides. I would much rather my guys take natural, less addictive stuff.”

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated and SI.com. He is also the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law and the distinguished visiting Hall of Fame Professor of Law at Mississippi College School of Law.