Inviting the Nightmare

AURORA, Ohio — Donte Stallworth wants to be in the correct frame of mind for tomorrow morning. Alone in a northeast Ohio hotel room, he flips open his laptop, pulls up a web browser and Googles himself.

“Donte Stallworth 911 call”

Stallworth: Ok, listen, listen ... This guy just ran in front of my car and he's [expletive] laying in the street dude ... I, I …

Dispatcher: So you hit somebody in the street?

Stallworth: Yeah, you gotta send an ambulance right now man. He ran in front of the car sir, he like, jumped in front of the car.

Oh no. [Expletive]. Oh my God, this guy is ... oh ...

This is the second time he’s listened to the tape. The first was several months after it happened. On an early morning in March 2009, Stallworth killed a man while driving drunk.

The nightmares have come and gone for five years now, and the daytime flashbacks sometimes return when he rides in a car. (All he does is ride now—he can’t obtain a driver’s license in Florida for the rest of his life.) Tonight, on the eve of his appearance as a speaker at the NFL’s Rookie Symposium, he invites the nightmare.

“It brought back the feeling of looking down and seeing a man lying on the ground motionless,” Stallworth says. “I needed to feel it again, if I was going to instill that image.”

What Stallworth did and didn’t do five years ago is a more complicated story than many of us care to know. There’s the story he tells the rookies, the story he tells me, and the story he tells himself. Somehow, all of it’s true.

* * *

Everything starts with Mario Reyes. He and Stallworth share permanent residence in one another’s obituaries. Stallworth accepts this. He views all of his own problems in the shadow of the Reyes family. His fingers are mangled and knobby, but Reyes is dead. His sleep is haunted, but Reyes is dead. He lost all of the money he’d made in the NFL, but Reyes is dead. He has post-traumatic stress disorder, but Reyes is dead.

He’s reminded of this fact every other day on Twitter. The keyboards of anonymous strangers point it out whenever he tweets a controversial opinion, as if he’s forgotten all about it. To be fair, I was once like everyone else. I always wondered how Donte Stallworth, NFL player, did just 30 days in prison for DUI manslaughter, and I could only guess at the degree of audacity required for such a man to tweet opinions and debate politics in the open.

Then I met the man, bubbly and grinning before turning serious over lunch at the Rookie Symposium two weeks ago.

“The insults come a few times a week. It comes with being open,” says the ex-wide receiver, now 33. “I respond every now and then but never in a negative way. It’s a lose-lose battle for me.”

Two weeks ago Stallworth tweeted his excitement over the opportunity to address rookies on the consequences of drunk driving. A woman shot back: You’re a hypocrite. How can you tell them not to do that when you did it?

He responded: So I can help my bros avoid the same fate.

* * *

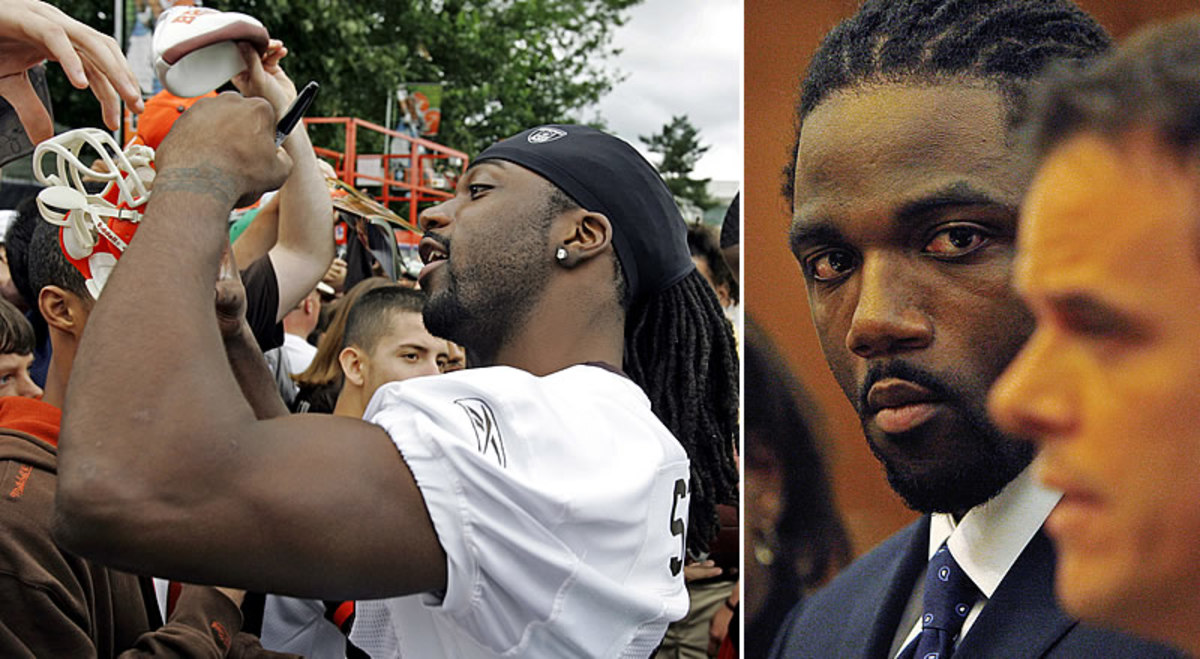

Stallworth took the podium in an amphitheater at the Bertram Hotel four times last week, flanked each time by the president of Mothers Against Drunk Driving. He delivered the talk he’d rehearsed in the hotel room. It has been nearly a year since he was last on a roster (Washington cut him last August), and he’s five years removed from March 14, 2009, the morning that delivered him here.

To pay the Reyes family, Stallworth had to sell the home he’d bought for his mother. But he doesn't think about the settlement. “[His daughter] won’t have her father walk her down the aisle. It’s a ripple effect. He had a family as well.”

Stallworth was a member of the Browns, having signed a seven-year, $35 million deal the previous March. It was the last weekend before the start of Cleveland’s offseason program, and he was spending it in Miami, where he still lives today. At 2 a.m. on Saturday morning, a friend called and said it was his birthday, inviting Stallworth out for drinks. Stallworth showered, dressed, and took his Bentley to the Fontainebleau hotel, about 15 minutes away from home.

“That was mistake No. 1,” he tells the rookies. “I knew I was going to drink, because it was a friend’s birthday, and I drove anyway. I had driven drunk before. It’s that feeling of having it under control.”

Stallworth enjoyed several drinks of Patron, then drove home and was in bed, asleep by 5:30 a.m. He slept until 7, then woke up hungry. He knew of one place open that early, the News Café, 15 minutes away.

“Right as I was crossing the bridge,” Stallworth says, “not even five minutes from walking out of my apartment, was when Mr. Reyes was running across the street to catch the bus. That’s when I hit him.

“Sometimes in your mind, you may think that if you’re not ‘wasted’ then you’re okay to drive. That’s the issue. You’re never okay to drive when you’ve been drinking.”

That’s the version Commissioner Roger Goodell heard last November at the league’s New York offices when Stallworth laid out what he might say at the symposium if given the opportunity. It’s cut and dry. But that’s not to say it didn’t resonate. Buccaneers tight end Austin Seferian-Jenkins got chills listening to Stallworth talk, bringing him back to his own DUI last year.

“You play that What if? game,” Seferian-Jenkins says. “What if I had killed someone? I was lucky that I didn’t die or hurt anyone. But Donte wasn’t, and it’s incredible that he can talk about it.”

Seferian-Jenkins and the rest of the NFC rookies didn’t hear the rest of the story, which is nearly as misunderstood as the man telling it.

***

He doesn’t look like an NFL player, with his slight frame and cheesy grin, until you get to his hands. They’re deformed the way a pass-catcher’s hands deform over the course of two decades in football, with crooks and bumps and bends all over. His left pinky is twisted and bowed outward, a victim of Bears cornerback Charles Tillman’s famous bump-and-run technique. During a preseason game in 2004, Stallworth’s finger lodged in Tillman’s facemask and when he yanked it loose it dislocated, tearing ligaments throughout. The brace hurt more than the original injury, so he decided to let it heal naturally; it didn’t.

Black tattoo ink spills from under the cuffs of his dress shirt, dotting his wrists and hands. He has a wedding ring tattooed on his left ring finger—a reminder that he’s married to himself, applied after a relationship went sour in 2012. “There was too much focus on her and not enough on me,” he says.

Introversion is near impossible for Stallworth. In Cleveland, he’d blast Frank Sinatra from the stereo in his locker as teammates rolled their eyes. In Washington, he advised teammates to examine Obama’s politics, and not to vote for him just because he’s black. He’d share political conspiracy theories during lulls in the workday, or buy a dozen copies of the latest government-related book he’d read and hand them out among teammates and staffers.

“He was always trying to make guys more aware of what was going on in the world and trying to get people to ask questions,” says former Browns director of communications Amy Palcic, who remains close with Stallworth.

When he hit Reyes, a construction worker trying to catch a bus home, it hadn’t occurred to him that he’d be investigated for DUI until they handed him a Breathalyzer at the scene. He blew a 0.126, above the Florida limit of .08. After his blood was drawn, he texted Palcic, “I need your prayers more than ever.”

Palcic joined Stallworth’s inner circle, which included attorney Chris Lyons, pal Steve Boucher and Rebecca Howard, an attorney married to Desmond Howard. Each exhausted their resources to keep him free. At first, he was facing more than a decade in prison if convicted of the charges at face value. But his squeaky clean background was considered, and he reached a settlement with the Reyes family, who would weigh in on the sentence.

Then the state’s prosecution analyzed a still-sealed traffic camera video, which showed Stallworth braking his vehicle immediately after Reyes ran into the street, outside of the crosswalk.

“The way everything happened,” he says, “I do feel that I would have hit him even if I was sober.”

So why, then, take full blame in front of the rookies and anyone else who asks?

“At the end of the day, I was wrong,” he says. “I was driving under the influence and should not have been. Anything after that doesn’t matter. I’ve accepted responsibility for it. If I wasn’t on that road it wouldn’t have happened, and if I wasn’t driving under the influence I wouldn’t have been on that road.”

* * *

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovSrvjx5ZiQ?rel=0]

There’s a strange, coincidental connection between Stallworth and one of the rookies he’s speaking to at this symposium. Bears rookie Brock Vereen, younger brother of Patriots running back Shane, was a high schooler enjoying his summer vacation when he got a call from his father the morning of March 14, 2009. The Vereens grew up in California, but Henry Vereen was in Miami for work as a video engineer. He was one of the first bystanders to see the aftermath, before police removed Reyes’s body.

“He was in shock,” Brock remembers. “He said he saw a body, and he was just amazed at how far away from the car it was. You see that kind of stuff in movies, not in real life.

“To hear Donte talk about everything at my symposium was crazy—the girl, especially.”

The Rookie Symposium

Every summer, the NFL's first-year players travel to a hotel in Ohio for a crash course on what life is really like in pro football. This year, we went too. PART I | PART II

“The girl” is the lone surviving child of Mario Reyes, now in her early 20’s. Stallworth is forbidden from contacting her or her family, due to a court order. In 2009, Stallworth agreed out of court to pay an undisclosed sum to the family. It meant giving up virtually everything he’d earned since the Saints drafted him in 2002—and yet, it didn’t feel like enough.

“She’ll be living with that for the rest of her life,” Stallworth says. “Her high school graduation, college graduation, she won’t have her father walk her down the aisle. People won’t necessarily talk about that, but it’s not just about Mr. Reyes or me. It’s a ripple effect. He had a family as well. I had a family.”

To pay the Reyes family, Stallworth last year had to sell the home he’d bought for his mother (she now lives with his brother). He continues to look for a job in media, having mentally—if not officially—retired from football.

When he thinks about the Reyes family, though, it’s not about the settlement. Two weeks after the accident, a representative for the family reached out to Stallworth’s attorney and asked to pass along a message: They were appreciative of how Stallworth owned up to his mistake.

“That gesture was one of the things that really helped the healing process,” he says.

Stallworth planned out the rest of his life: First, earn forgiveness from God, then from the Reyes family, then from his own family, then from the NFL. Finally, save fellow NFL players from making the same mistakes.

“That family made me feel like I had to get the message out,” he says, “because if they can forgive me, then I have a responsibility.”

* * *

Blue ink on white notebook paper. The prison letters were written in a solitary cell at a Miami-Dade jail. Stallworth spent nearly every hour in isolation during his 24 days because he was too high-profile for general population. Over the first few days, he spilled his heart to Palcic on paper, having accepted that his name would be attached inexorably to the manslaughter.

I not only have to battle being known only as a pro athlete, but as a pro athlete who pled guilty to DUI manslaughter. It’s all good, though. I’m in here cooking up a game plan on how I can get that done, so when my time expires, it will be Donte Stallworth, a man who accomplished great things while he was here, had a speed bump, but excelled through the controversy and left a great impression on the world.

The way to that goal, Stallworth acknowledged, was not clear then, and still isn’t now. He didn’t anticipate the nightmares five years later, or the NFL-mandated therapist who would become his full-time resource. Four years after the league suspended him for a full season, and the Browns cut him one year into that big contract, he’s still on probation (until 2017) and still struggling financially. When Washington cut him last August, he sulked around his place in Miami for a few weeks before committing himself full-time to media opportunities and projects like the symposium.

After his session, a player approaches him and quietly asks if he felt drunk when he woke up. “No,” Stallworth answers. “If I had been asked to walk a straight line, I would’ve walked it.”

“I think he’s finally able to wrap his arms around the responsibility he feels,” Palcic says. “I think he can look back and understand all the mistakes that led him to that night. Being done with football is part of that.”

Stallworth is in preliminary talks with the NFL about signing on as a speaker for individual teams. In past seasons, he’s addressed the Ravens, Patriots and Washington in much the same way he did the rookies last week. The reception has been good so far, though it’s rare to see his efforts immediately validated. After Stallworth expounds on the consequences of his actions, there aren’t typically enough questions for a Q&A. The subject matter is just too raw. It’s in quiet moments in locker rooms and cafeterias that Stallworth gets feedback, and hope.

After his Tuesday symposium sessions, an NFC first-rounder approached Stallworth quietly to ask several questions. Among them: “Did you feel drunk at all when you woke up at 7 a.m.?”

“No,” Stallworth told him. “If I had been asked to walk a straight line, I would’ve walked it.”

Stallworth finished his final presentation at the AFC symposium with a quote from 19th century German chancellor Otto von Bismarck: “Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others.”

The story Stallworth tells himself is simple: Play the fool, save a life.