Goal-to-Go: Should NFL Teams Pass or Run?

Keith Goldner

The Eagles lost their first game last Sunday, falling to the 49ers, 26-21. Phildadelphia coach Chip Kelly made a series of tough decisions, but his play-calling near the goal line during the Eagles’ final drive has been the most criticized. The game essentially came down to a first-and-goal from the 6-yard line, followed by third-and-goal and fourth-and-goal from just beyond the 1.

On first down, quarterback Nick Foles threw an incomplete pass targeted at Jeremy Maclin. On second down, LeSean McCoy ran off left tackle for a five-yard gain. Then, the Eagles passed on their final two downs, both falling incomplete.

Tony Dungy made his opinion clear on Sunday Night Football, saying the Eagles should have run the ball at least once, if not twice, because they were on the doorstep of the end zone. Kelly’s teams have always been known for their ability to efficiently run the ball, and the Eagles have one of the best running backs in the league in LeSean McCoy—not to mention Darren Sproles.

Dungy’s remarks seem logical.

Then again, the 49ers are known for their run-stopping defense and the Eagles were unable to move the ball on the ground all game, mustering just 21 yards on 11 carries. McCoy had 10 of those rushes for 17 yards, while Sproles ran once for four.

Goal-to-Go: Should NFL Teams Pass or Run?

Nick Foles’ third-and-goal pass to tight end Brent Celek fell incomplete ... (Jed Jacobsohn/SI/The MMQB)

... as did his fourth-down throw to wideout Jeremy Maclin. (Jed Jacobsohn/SI/The MMQB)

In a pass-happy league, what is the best strategy in goal-to-go situations? And how does it change based on the distance to cover? To answer these questions, we looked at more than 30,000 goal-to-go situations since the 2000 NFL season.

To evaluate each play, we looked at touchdown conversion rates as well as our internal metric, Net Expected Points (NEP).

A quick refresher: NEP compares every single play over a season to how a league-average team should perform on that play. Every situation on a football field has an expected point value; that is, how many points an average team would be expected to score in that situation (given down, distance-to-go and yard line). For example, the Chiefs may be playing the Steelers, facing a third-and-two on the 50. That’s a ton of variables, but numberFire has data from every single play dating back to 2000, so most situations have come up at least once. According to our data, an average team may be “expected” to score 1.23 (estimated number) points on that drive. However, Jamaal Charles reels off a 32-yard run to bring the Chiefs into the red zone, increasing the “expected” point value of the next play to 4.23 (still an estimated number). Jamaal Charles then gets credit for the difference, in this case 2.96 points, as his NEP total. That’s Net Expected Points.

To judge efficiency, we look at NEP on a per play basis as well as a metric known as success rate. Success rate is simply the percentage of plays for which the NEP was greater than zero—plays on which the team performed above average.

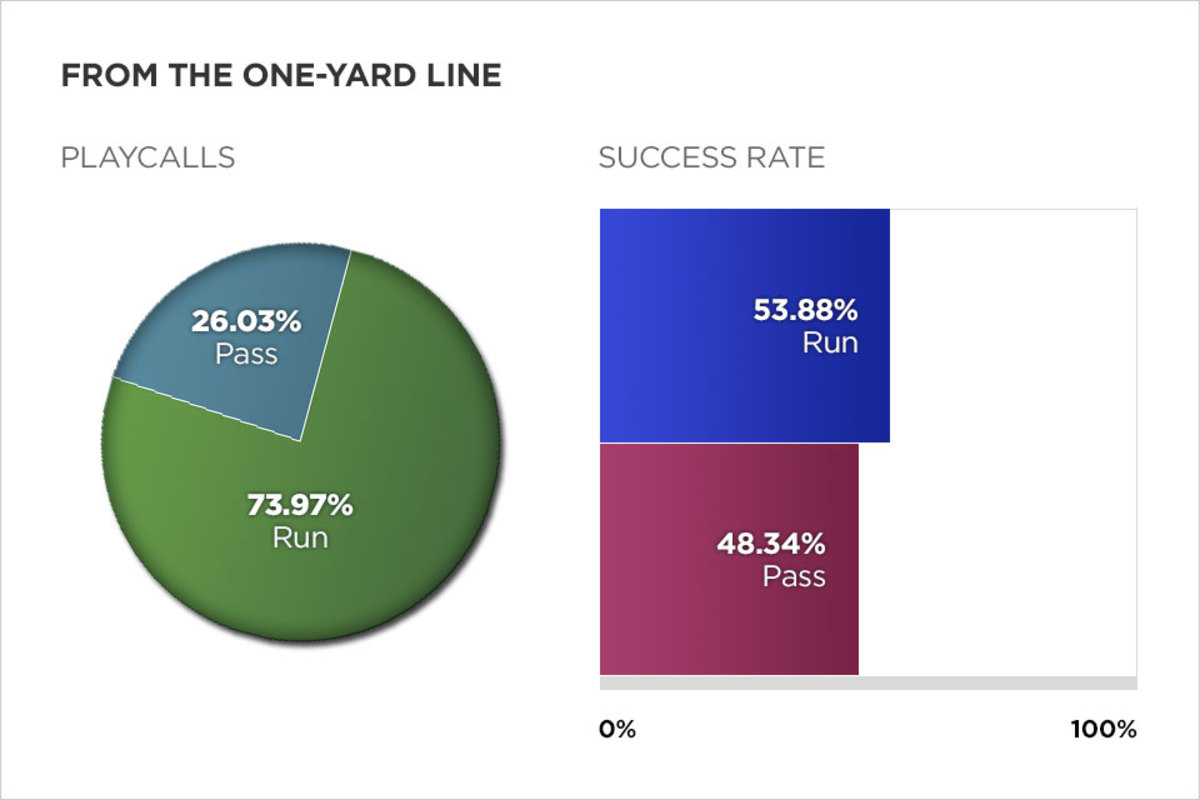

Teams on the 1-yard line have run the ball 73.97% of the time since 2000 and are successful 53.88% of the time. Teams passing from the 1-yard line have posted a 48.34% success rate. Being so close to the goal line, success almost always means scoring a touchdown—though there are a few penalty situations that could be considered a success.

Another thing to notice is that the NEP per play running the ball inside the 10 is almost always higher than passing the ball. This is because the potential for highly negative outcomes is much higher on passing plays. There were 28 defensive touchdowns on passing plays in the data set compared to only seven defensive touchdowns on rushing plays—a long pick-six is much more likely than a long fumble return. Because of this skewed distribution, it makes more sense to use the success rates to evaluate play calling.

We can also look at one-play touchdown rates to gauge success. But keep in mind, on early downs, teams are not necessarily trying to score on that play.

Not surprisingly, as you move away from the end zone, teams have a greater chance of scoring if they throw the ball. That said, running the ball on the goal line is generally the more efficient option.

It’s easy to criticize one play call or even a series of play calls, especially after a bad result. There are myriad external factors that a head coach also considers: How has my team been running and throwing the ball today? How are my players feeling? What formations are going to be most successful? How does the defensive alignment dictate my play-calling? The list goes on and on.

It’s also essential to evaluate a decision based on the process that takes place before the trigger is pulled, rather than the outcome. In the NFL, we are always dealing in probability—just because the coin comes up tails does not mean it was the incorrect decision.

Unfortunately, a single play in a 16-game season can have a tremendous effect on a team’s playoff and Super Bowl chances. Just ask the Steelers, who skipped the playoffs after Ryan Succop missed a game-winning 41-yard field goal against the Chargers in Week 17 last season.

Such is winning in the NFL, in all its ephemeral glory.

Keith Goldner is the chief analyst at numberFire.com, the leading fantasy sports analytics platform. Follow him on twitter @keithgoldner.