Game-Planning the Patriots: An Insider’s View

The Jets held Brady to under 200 passing yards in the narrow Week 16 loss. (Al Tielemans/SI/The MMQB

From October through Thanksgiving, the Patriots offense tore through opponents. During a seven-game win streak, New England averaged just shy of 40 points per game—that’s five touchdowns, a field goal and more.

But the machine can be slowed. The 3-11 Jets did it in Week 16. The Patriots won that day in New Jersey, but their output, 17 points, was their lowest with a healthy Rob Gronkowski and Tom Brady playing the full game this season. “If you can control Brady—I don’t know if that’s really possible,” Rex Ryan said afterward, in a parting shot a week before he was fired as Jets head coach, “but if not, we’re the team that always gives him his biggest challenge, whether he admits it or not.”

There’s truth to that statement. An ugly 45-3 loss back in 2010 notwithstanding, in the 13 times the Jets played the Patriots during Ryan’s six-year tenure, New York found ways to flummox Brady with pressure up front—real or perceived—and mixed coverages. The Jets were responsible for two of Brady’s four lowest passer ratings during that span: 53.1 in a Jets win in New Jersey in 2009 and 53.5 in another Jets home win in 2013.

So this year, with the road to the Super Bowl for the AFC again running through Foxborough, The MMQB tapped the insight of Ryan’s defensive coordinator and co-schemer, Dennis Thurman. How do you game plan for Tom Brady and the Patriots?

Start with stopping the run. The Patriots’ running backs may not be New England’s most-renowned weapons, but the defensive game plan starts here. “It has to be your number one priority, because they can run the football effectively, and if you let them you are going to have a long day,” Thurman says. “Because now you are going to have to put that extra guy in the box, and play more single-high coverage and man-to-man on the outside, and they are really good at exploiting matchups.” True to form, at halftime of the Week 16 Jets-Patriots game, running back Jonas Gray had just three carries for four yards. The Jets, much like the Patriots’ opponent in the divisional round this week, the Ravens, had a strong front seven, so the key was winning up front and players getting off their blocks and making sure tackles.

Clamping down on the run game disrupts the Pats’ ability to use play-action, at which Brady excels. (Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Stopping the run also helps thwart the Patriots’ play-action passing game, which is a big part of their offense. Per Pro Football Focus, 26.3 percent of Brady’s dropbacks were play-action plays, the fifth-most in the league, and he completed 101 of those passes for 1,366 yards, highest in the NFL. “They can get the ball vertically down the field, especially to their tight ends and to their slot off play-action,” Thurman says. One reason their play-action game is so good is that it marries up to their run game, which is the goal of play-action, but not always achieved. “It looks like one of their runs. You’ve got your eyes in the backfield, and now they are hitting you with a pass off play-action because you are playing with bad eyes,” Thurman adds. “If they can run the football against you, they’ll be able to play-action pass, and they’ll be able to throw the football, and pretty much do whatever they want to do.”

Blitz because you want to, not because you have to. “It’s hard to really pressure [Brady] with blitzes because he doesn’t hold the ball long,” Thurman says. “You are asking for trouble over time if that’s your game plan.” Brady averaged just 2.39 seconds from snap to throw this season, per Pro Football Focus, faster than every quarterback in the league other than Peyton Manning (2.24 seconds). Despite turnover on the offensive line (see: Logan Mankins trade), New England gave up just 26 sacks this season, fourth-fewest in the league. So how do you get to Brady? “If you are getting pressure from your front four, that’s the ultimate,” Thurman says. “And when you design pressures, some are designed to get home, some are designed to put pressure up the middle and in the quarterback’s face, and some are designed to beat the protection you believe they are going to be in at a certain point in time in the game. It’s a matter of getting the pressure you want.”

The Week 16 game is a good snapshot of what he’s talking about. The Jets sacked Brady four times in the first half, as many times as he had been sacked in the eight previous games combined. Two were simply the players up front winning their one-on-one matchups and beating the offensive linemen blocking them. The other two were schemed up. On the first, which ended New England’s first drive, the Jets showed three defenders standing over the right side of the line pre-snap, so the Patriots slid protection that way. But the Jets instead pressured from the left, leaving left tackle Nate Solder alone against three rushers. Calvin Pace, who came off the edge, and David Harris, who crossed from the other side of the formation, sacked Brady.

The Jets scrambled their looks—here stacking three defenders to make it appear the pressure would come from Brady’s right, but then dropping those three and bringing Pace in free from the left for the sack. (NFL Rewind)

Later in the first quarter the Jets used deception again. Safety Antonio Allen lined up five yards off the line, but when Brady raised his knee to trigger the snap, Allen took off sprinting toward him. Gronkowski, in position to block linebacker Demario Davis, turned away from Davis as Allen ran past. Both got through and split the sack. “It comes down to timing,” Thurman says. “And understanding the snap count.”

Disrupt Gronkowski. The Jets put on film a pretty good plan for slowing the unanimous All-Pro tight end. Gronkowski scored a touchdown against the Jets, but they held him to six catches for 31 yards, matching his previous season-low in yardage, which came against the Chiefs in Week 4 when he still wasn’t at full strength after offseason knee surgery. “The first thing is, you pay attention to him,” Thurman says. That seems simple, but opposing defenses didn’t always do that this year. Know where Gronkowski is on the field, and do everything you can to disrupt what he is doing and where he is trying to go. “Distract him and get extra little hits on him; bump here, bump there,” Thurman says. “Make him run off of his course. Throw the timing off between him and Brady.” The Jets usually did that by lining up an outside linebacker on Gronkowski at the line of scrimmage, to push him as he came off the line.

The second part of the plan was to bracket coverages around Gronkowski. “There are different ways of doubling based on where you are on the field,” Thurman says. “Sometimes it’s inside and outside; the other way is to have somebody underneath and somebody over the top, along with somebody trying to get their hands on him before he gets started. He’s that good to draw that much attention.” Here’s one example: Right before halftime, the Patriots had the ball deep in their own territory with 48 seconds left on the clock. Brady was looking for Gronkowski, but the Jets had him bracketed: linebacker Harris bumped Gronkowski out of his break and undercut the route, and New York had a safety over the top. While Brady was looking, defensive tackle Sheldon Richardson beat his block for a sack, and the Patriots kneeled out the clock.

The Jets bracketing Gronkowski, who had just 31 receiving yards, tied for his lowest production of the season. (NFL Rewind)

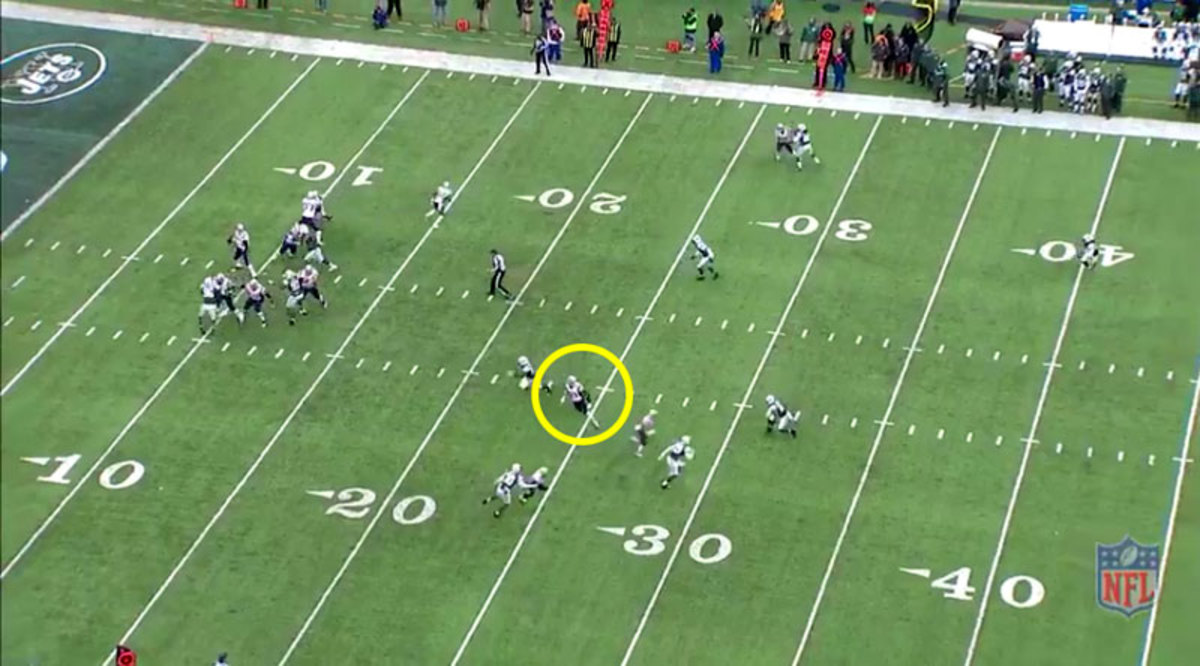

The Patriots try to avoid double coverage on Gronkowski by splitting him out wide. That’s the spot from which he scored his touchdown against the Jets, matched up one on one against rookie safety Calvin Pryor. But in other instances cornerbacks Darrin Walls and Marcus Williams, an undrafted rookie, fared well one-on-one with Gronkowski outside, using their hands inside the five-yard bump zone and clinging to him in coverage.

Key for a cornerback to slow Gronkowski (in yellow) is getting a good chuck in at the line. (NFL Rewind)

(Side note: The Ravens, like the Jets, have had to go deep into the well to staff their secondary. What do you tell an undrafted rookie covering Gronkowski? "There’s an age-old saying in the NFL: You respect everybody but you fear no one," Thurman says.) One benefit the Jets had that the Ravens will not this week was the absence of top receiver Julian Edelman, who’d been sidelined with a concussion. “It made it easier because [Edelman] wasn’t part of the equation,” Thurman says. “Otherwise, they can work their tight end on linebackers and safeties, [Shane] Vereen is coming out of the backfield, and then you have to pay attention to Edelman outside with your corners.”

Patriots in The MMQB

Revis Unplugged: On joining forces with Belichick and Brady, Rex Ryan, and bump-and-run vs. the NFL's eliteSame Old Gronk—or Maybe Better: A stunning return to dominance after two years battling injury highlighted the dedication that was mostly lost amid his party persona.Brady through the eyes of former teammates

Remember that they’re creatures of habit.

One reason the Patriots offense is unique is that it morphs week to week based on the opponent—one week beating the Colts with a power-run game and the next throwing the ball 53 times against Detroit. That seems as if it would make game-planning especially challenging for the opponent, right? “You can talk about being game-plan specific, but there are certain core things you’re going to do every week,” Thurman counters. “You have to look at the human side of it, that coaches are people, and people are creatures of habit. They are going to do certain things at a certain time from a certain position on the field, and your ability to anticipate those, and to study those as part of your preparation, becomes as big as anything.”

Coaches guard tells and tendencies like Fort Knox, but Thurman gave one example of a core concept the Patriots always have in their hip pocket: the screen game, particularly to their receivers. “Whether they’ve done it and how much they’ve done it before they play you, you know it’s something that’s very important to them,” Thurman says. “And they may not throw one early in the game, but they’ll throw one late, and all of a sudden you’re not prepared for it because they’ve lulled you to sleep. They’ll get big chunks, or a key first down at a time when you’re like, there’s no way.” He knows, because it happened to the Jets in Week 16. The Patriots were trying to preserve their one-point lead and needed a first down on a third-and-7 with 4:38 left to go in the game. Receiver Danny Amendola hadn’t caught a screen all game, but they dialed it up there, and he got the first down.

Don’t look at the personnel on the field, look at the final picture. The Patriots have those core concepts they use every week, but they’re very good at changing how they get to them. “It varies game to game, and that’s part of the intrigue,” Thurman says. Here’s an example: One week, they may use 21 personnel (one running back, one fullback, one tight end and two receivers), motion the back out of the backfield to create a two-by-two set, with two receivers on each side of the formation, and run a pass route. The next time they run that pass route, it’s out of 12 personnel (one running back, two tight ends, two receivers). Another time, they run the same route out of 11 personnel (one running back, one tight end and three receivers). “You know they like this pass route, but you’re trying to figure out, how are they going to get to it,” Thurman says. “You have to remember that the two-by-two look is more important than who’s doing it.”

Make Brady do some thinking. “There’s nothing he hasn’t seen already,” Thurman says. “But at the least, you want him to have to do some thinking, and have to do some reading, once the ball is snapped.” That’s why the Jets defenses under Ryan have had some success against Brady: They disguise pressures and coverages, and show one thing before the snap and do something else after it. Another rule of thumb: Try not to do any one thing more than any other. “Over time, we’ve tried to be more multiple in how we do things and give them a changing picture,” Thurman says. “We may bring one certain concept for a half, and then try to change and do some things differently the second half.”

The best example: During the 2010 season, the Jets beat Brady and the Patriots in the divisional round in Foxboro with a game plan that looked nothing like the one they used in their 45-3 loss just six weeks earlier. The Jets activated 11 defensive backs for the game and introduced four new coverages (one, the brainchild of safety Jim Leonhard) that packed the DBs in the middle of the field to limit Brady’s options. “That was a one-time thing,” Thurman recalls. “We felt like they thought we would stick with the same game plan that we had used the two prior games, and that all we would ask our guys to do is play better. We were able to spring it on them that time and had success.” The Jets won, 28-21, to go to the AFC Championship Game. But Thurman still recalls Brady starting to figure it out toward the end of the game. “Fortunately,” he says, “we were able to hold them off long enough.”

* * *

The Patriots’ opponent this week, the Ravens, have also demonstrated an ability through the years to throw Brady off his mark. Twice in the last six years the Ravens have knocked the Patriots out of the playoffs. And Brady’s lowest passer rating in that time frame? It came at the hands of the Ravens: 49.1, in Baltimore’s 33-14 wild-card round win against Brady in the 2009 playoffs.

The Ravens’ defensive coordinator, Dean Pees, might be one of the few defensive coaches in the league who knows Brady better than Ryan and Thurman. From 2004 to 2009, as the Patriots linebackers coach then defensive coordinator, he watched Brady in practice every day. Still, that doesn’t completely demystify one of the biggest defensive challenges in the league: Game-planning for Tom Brady.

“There aren’t any magical coverages,” Thurman says. “It’s when you do what you do as much as anything. And there are some secrets you have to keep in your pocket.”

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]