Maseratis, Hookah Bars and Cash by the Bagful: On the Trail of the $10,000 Super Bowl Ticket

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. – It’s 10:14 p.m. Mountain Time on the eve of the Super Bowl, and the man with a Miami Heat championship ring on either hand scrolls through his smartphone over a Grey Goose and club soda. Hookah smoke wafts through the air of the darkened bar and out onto the buzzing street. For the first time all week, the numbers are telling Michael Lipman something he wants to hear.

“I’m feeling ballsy right now,” he declares over the wobbling dubstep soundtrack. “Anything under $10,000, I’m buying seats. I’m stockpiling seats. I’m running this show now.”

Lipman and I have been riding around the greater Phoenix area for three days now. We went to a Bank of America branch to pick up so much cash that Lipman brought a backpack to carry it all. We’ve pulled up to swanky hotels alongside rented Italian sports cars to hand a paper bag filled with stacks of $100 bills from the window. We’ve met Black George, Indian Steve and Arizona Nick, names as recognizable in the ticket resale business as Brady and Sherman and Wilson are to the football viewing public.

The pros are here in Arizona, setting up shop in hotel conference rooms, memorabilia stores and private hotel lounges for the first $10,000-a-ticket Super Bowl.

If it all sounds somewhat sketchy, that’s because it used to be illegal. Lipman, who moonlights as a professional poker player, got into the game when most states still forbade the reselling of tickets above face value. In the early ’90s, before he became a broker, Lipman was a Boston University graduate running a high-class food service, delivering takeout to guests of five-star hotels in the Miami area after room service closed for the night. Then the car driven by one of his tuxedo-clad couriers broke down on the way to a luxury hotel in Coconut Grove in January 1995, just before the 49ers plastered the Chargers in Super Bowl XXIX at Joe Robbie Stadium. Lipman drove out to his courier’s car, retrieved the order and delivered it to the hotel. There he observed concierges dealing Super Bowl tickets that they’d purchased at a $200 face value for $1,800 apiece. Lipman called a client—the member of a prominent Miami sports family—in hopes of getting in on the action.

Bradyu2019s Best

The Patriots quarterback breaks down the final pulse-pounding quarter of Super Bowl 49 for Peter King in this week MMQB column. FULL STORY

Yes, they had some tickets, he was told, but they were the $300 seats, and they wanted double for them. Said Lipman: “How many do you have?”

Ticket brokers often equate success with the properties they purchased following big events. Seventeen months after that Super Bowl, Lipman bought his first house exclusively with money earned during the four-game 1996 NHL Finals between Colorado and Florida. Back then the hustle boiled down to buying face-value tickets, waiting until demand hit the sweet spot, then unloading the haul out of view of the police. But the game has changed. By the mid-2000s every state legalized reselling, and StubHub and other online brokers had become a common part of the ticketing process. Leagues turned to Ticketmaster and other major sites to determine the true value of their offerings on the secondary market. The 2008 recession also caused corporations to cut back on extraneous spending such as box seats and suites for the local teams. In 2001, seeing the writing on the wall, Lipman launched Tickets of America, an online service, and in 2004 he shifted his focus to high-brow clientele with a company called White Glove Entertainment. Business moguls and recording artists call on White Glove, an official partner of the Miami Heat, to take care of them. Lipman’s company offers not just luxury tickets but hotel arrangements, travel accommodations and opportunities to meet players. Hence, those Heat championship rings.

Lipman and his Tickets of America/White Glove staff once dug in at a Super Bowl with up to 1,200 ticket orders. At this one they’re satisfied with a few hundred. For Lipman and his longtime partner, Ayeh Ashong, the Super Bowl harks back to a simpler time. It’s a taste of the old hustle, when you could quintuple your money on a single ticket.

“We were making a lot more money,” Ayeh says, “when this was illegal.”

* * *

The office. (Jed Jacobsohn for The MMQB)

I meet Lipman’s team at the epicenter of the brand-soaked official Super Bowl festivities, the Renaissance in downtown Phoenix. It’s Wednesday, and every other stranger I’d encountered on the 45-second walk from the media hotel to the Renaissance has the same question: Selling any tickets?

Four days before the game, the price for a Super Bowl ticket on the secondary market has climbed to $6,000, approaching an all-time high. Face value for Super Bowl 49 ranges from $800 to $1,900.

Lipman, Ayeh and their hospitality guru, Phil Calloway, sit in a quiet section of the 11th-floor lounge in front of their laptops. Ayeh could be a Cee-Lo stand-in if he never had to open his mouth and speak, revealing a raspy voice. Phil, a former college basketball player and middle school teacher, constantly checks his two smartphones for messages, responding to a handful of inquiries every time he picks one up. Lipman, 46, wears a black Oregon Ducks hat, red Nike tracksuit with white chest hair poking out, and those two rings.

He explains the resale market in its current form.

- The men I had encountered outside are known as “diggers.” They’re the cold-callers of the industry, hoping to cop a fan’s extra ticket or offer a tourist lower-than-market cash in exchange for the seat.

- The diggers then trade up with the bigger fish—Lipman figures there are two dozen or so major brokers in Phoenix for the game—who either fill their existing orders or wait until the market peaks and unload tickets online.

- Lipman, however, doesn’t normally deal with diggers; he wants to know the source of the tickets, to avoid scams. Thus most of his tickets come from corporate entities such as league sponsors, or from players.

Here’s where it gets tricky: Players and coaches are forbidden by league rules from selling tickets at a value higher than face, yet there is little to no regulation. Every player in the NFL has the option to buy two tickets to the Super Bowl. Players on the Super Bowl teams have larger allotments, and the system for distribution varies from team to team. (The league caps the tickets per player at 15). The Seahawks, for instance, allotted 13 tickets to each player—two complimentary and 11 available for purchase at face value of $1,500 for this Super Bowl, according to those interviewed by The MMQB. (The Seahawks and Patriots did not respond to e-mail requests for comment.) If not claimed, the tickets go back to the team owners, who then pump them out to sponsors and the like.

“Somebody’s gonna make money off of it,” one Seahawk says, “so why shouldn’t we?”

“You can make anywhere between $3,000 and $4,000 on each extra ticket,” said one Seattle defensive player, who asked for anonymity. “I sold eight. Some go to teammates, but most guys hand their extras off to agents, who sell them for a small cut. Pretty much everybody knows about it now. Word travels fast.”

A league spokesman told The MMQB that if a team’s employees were found to have engaged in reselling tickets at above face value, those individuals and the club would be fined.

Said a Seattle lineman: “I don’t see anything wrong with it. Somebody’s gonna make money off of it, so why shouldn’t we?”

Coaches have largely stayed away from the resale game since 2005, when Mike Tice, then the Vikings coach, and two assistants were caught reselling tickets; Tice was fined $100k by the league. But many players, with lower profiles and the requisite buffers between them and the broker, don’t blink.

On Wednesday, Lipman has 80% of his online and corporate orders fulfilled, meaning he has the tickets in hand or in agreement. He’s waiting on buying the rest as the market hovers around $6,000. Spending that much to fill a ticket order sold two weeks ago for $3,500 is a hit he’s not yet willing to take. Players or corporate sponsors, Lipman’s preferred sources, are more reliable than brokers and tend to sell for less than the market price that his fellow brokers would charge.

“This has been one of my most conservative years,” he says, “and thank goodness, because I would have lost a lot of money. What made me nervous about aggressively taking orders was the potential for this being a huge ticket. Then Seattle made it, and it was.”

* * *

Working the phones in Phoenix. (Jed Jacobsohn for The MMQB.)

We’re flying down I-17 North, cash resting on the back seat of the rental. Phil drives too fast for a guy listening to directions, texting and taking phone calls during the late-morning Thursday rush hour. There’s a FedEx package waiting at the Residence Inn on North Black Canyon Highway, containing a crop of tickets delayed in arriving by snowstorms in the Northeast. Delivery men and hotel workers have stolen tickets before, so better to pick them up ASAP.

Lipman fields a call from a New York area code.

“No, I’m not buying or selling tickets today,” he says. “It’s a bloodbath. Let me see if I can get you a seat. No, look, the phrase ‘good deal’ and this Super Bowl don’t go together. I’m gonna try to get you something that’s not exorbitant.”

The caller, Phil says, was a rep for two dozen Orthodox Jewish men who made their bones in the diamond business. They have a private jet gassed up and ready to fly to Phoenix if they can secure seats for the right price. Lipman won’t take the order until the market drops or he fulfills his existing orders, or they come up on their price. He made the mistake a year ago of buying in early. Ticket prices for the New York/New Jersey Super Bowl plummeted as the game approached, and he lost money. He’s holding out hope these prices will drop, for a number of reasons.

- “In a way, the market is being manipulated because the people who have a lot of seats are taking the seats off the system, so people are panicking. It’s brokers panicking among brokers, so it’s not a true market.”

- Also, “many corporate tickets and player tickets won’t become available until tomorrow, when people arrive [or don’t arrive] in Phoenix to claim them.”

- “The NFL holds on to certain seats that they’ll only release Sunday morning.”

- “The last time the market didn’t drop on Saturday night and Sunday morning was when [the NFL] sold a section of seats at Cowboys Stadium that didn’t exist.”

- The Phoenix Open PGA tournament "brought in a lot of wealthy visitors who had the means to go to the game.”

As Lipman explains this, Phil takes a call on one of his phones. A Russian somebody wants tickets to the Oscars but doesn’t want to provide organizers with his name or birth date.

“It’s real,” Phil tells Lipman, “but he got all bugged out about the security check. I guess it depends on how bad he wants to go to the Oscars.”

Lipman takes another call, this one from an NFL agent. A Pro Bowler requires game tickets, a driver on-call 24/7, a five-star hotel room for his wife and economical accommodations on the other side of town for his girlfriend.

Check. Check. Check. Check.

“You strapped?” the agent asks Phil. He laughs it off. “Would it make you feel better if I was?”

We arrive at the Residence Inn, and Phil begins prepping rooms for their customers who ordered a package—tickets, hotel, tailgate party. Lipman takes a short nap and wakes up in time for a knock on the door. Dressed in Miami Hurricanes pajamas, he greets a financial planner from Boston who reserved tickets online with an American Express Platinum card.

“I deal with everyone,” Lipman says. “I try to be Switzerland.”

The card gets the buyer into the hotel room with Lipman—not every client gets such personal treatment—and three tickets for $5,000 apiece, which Lipman says he originally procured from a Patriots player. The man reserved the tickets days earlier, before the prices jumped to their current $8,500.

It would have been within Lipman’s rights, according to the online fine print, to refund the buyer his cash and decline to provide the ticket, instead selling it to another person at its new rate. This is called a busted order. Sweepstakes and contest winners often take the deal happily. Most people don’t realize that their tickets aren’t guaranteed, and several hundred arrived in Phoenix to find their tickets weren’t theirs anymore. Refunding 200% of the cost is the industry standard, and some companies have no qualms about busting orders when the market booms. Lipman would rather take his lumps and keep his good reputation.

Super Bowl 49

A look back at the best coverage of this year’s Super Bowl from Peter King and the rest of The MMQB team, on our Super Bowl hub. FULL STORY

“It’s pure greed, and you’re seeing a lot of it this Super Bowl,” Lipman says.

Already he’s heard of one broker who busted an order for $1,800 a ticket and only refunded the agreed price rather than double it. Then the broker checked into a new hotel to avoid encountering the customer.

“They sell it off of some website they’re never going to use again,” Phil says, referring to pop-up sites that are created for a single big event. “Then there are layers between their name and what they did.”

The sun sets on the valley, and we’re still running. To Phoenix and Scottsdale and Glendale. Pick up tickets here, drop off there. We arrive at the W in Scottsdale and park out front as Maseratis and tricked-out Chevy muscle cars pull through the circular driveway. An agent emerges from the crowd milling in front of the hotel, and Lipman grabs a paper bag full of cash and exchanges it for player tickets through the passenger-side window. It’s taboo to ask which player owned the tickets if the seller doesn’t offer the information, but Lipman has an educated guess.

The agent looks at the backpack, then at Phil and Lipman.

“You strapped?”

Phil laughs it off. “Would it make you feel better if I was?”

We’re on the road once more, heading to a late-night meeting at Jaguars, a gentlemen’s club, with a well-propertied restaurateur worth more than $400 million. Before Lipman joins the suit in the VIP section, the rep for the Orthodox group calls again, and Lipman is brief with them.

“You wire me a quarter of a million right now, and I’ll guarantee a suite for all 24,” he says.

No deal.

* * *

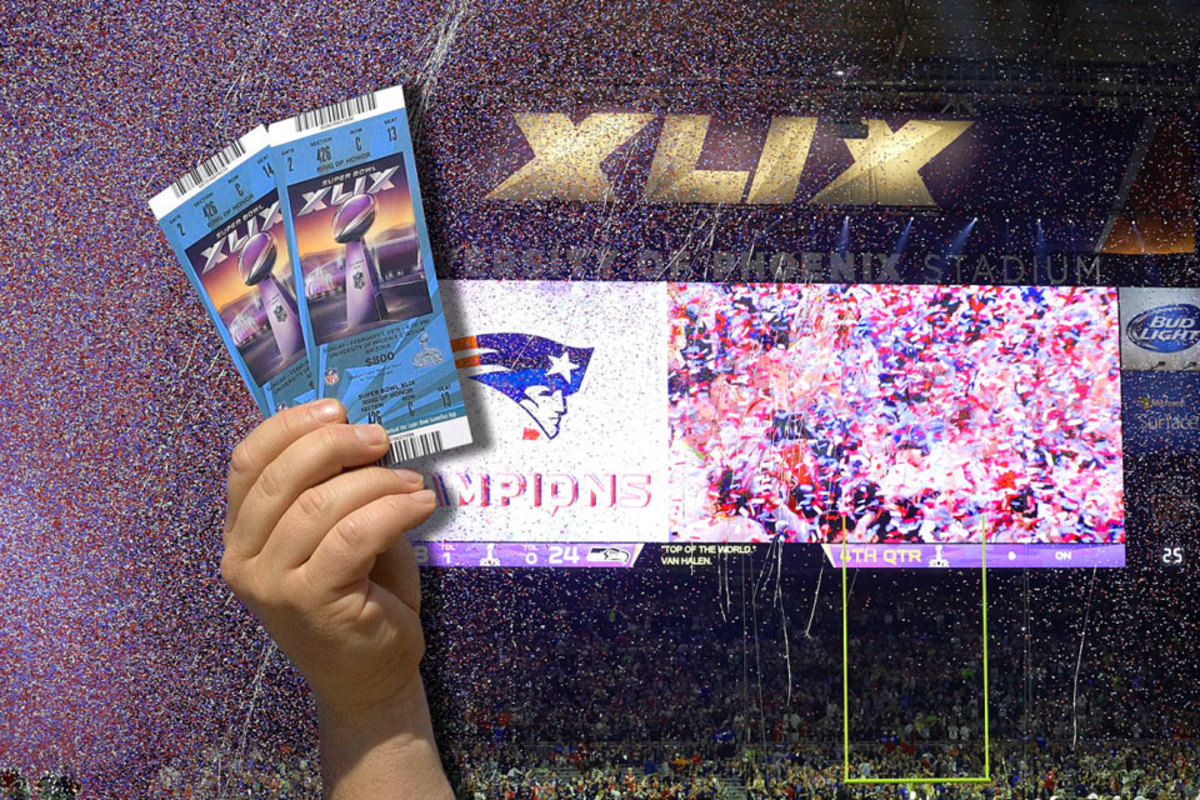

Face value of tickets ranged from $800 to $1,900. (Donald Miralle for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Phil is a basketball guy at heart. At 6-6, he felt obligated to play college ball but ultimately couldn’t emotionally commit to making an impact at FIU. He earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology, then a master’s in sports management from Barry University before landing a job as a middle school special education teacher in Miami, where he coached hoops. One day three years ago he was coaching against Lipman’s son Jacob and impressed the local business mogul. Lipman invited Phil to coach his AAU Elite Youth Basketball Organization team, the Nike South Beach All Stars. Soon Phil left his job to join White Glove and Tickets of America.

He is a man of few words who rolls his eyes at some of Lipman’s quirks yet ultimately cedes to his judgment. Phil draws from his experience as a middle school coach in handling customers.

“It taught me how to deal with these high-maintenance, wealthy people because I had their kids on my team,” he says.

Phil arrived the same year that Tickets of America pulled out of the National Association of Ticket Brokers. Ayeh says it was because the organization offered only limited funds in a fight against proposed Ticketmaster-backed legislation in Florida that would have given exclusive resale and presell privileges to the seller (often, Ticketmaster). That bill failed under opposition from the newly-formed Florida ATB, backed by Lipman and others. They chose to maintain the customs of the national association, including the honoring of verbal agreements and the 200% refund.

The internet and the lawmakers have mussed up the game, yet to hear Lipman or Ayeh in negotiation for something as trivial as a pass to a Saturday night Super Bowl party is to understand how sacred the hustle remains to these bastions of a once-wild west. Standing in a doorway at the Hyatt House in Scottsdale, Ayeh delivers a Saturday night order to another broker, then asks the rep if he has DirecTV party tickets.

“Yeah, I got two.”

“Can you get three?”

“I can rustle up one more.”

“How much you want for them?”

“Anything really.”

“What’s a realistic number?”

“250 apiece.”

“Three for $500?”

“Done.”

The rep leads us to a well-lit conference room with a temporary table housing six laptops, all manned by under-30 brokers and assistants. We’re not 20 feet away from the door when Ayeh leans in and tells me: “They’re going for $900 right now.”

On Saturday night, prices have dipped to $8,600. Brokers are busting their orders and putting a surplus of tickets back on the market. Time to buy.

Around 10 p.m. Lipman and I get dropped off at the W, where a party featuring Jamie Foxx and Drake rages inside, and someone is supposed to deliver Lipman more tickets to fill his last order. Rather than stand outside among men in designer skinny jeans and women in scant minidresses, we dip into a nearby hookah bar for dinner. Lipman has slept no more than four hours in each of the last three nights, and he’s staring at online exchange rates the likes of which he's never seen. In the afternoon they sat at $10,000; now, however, they've dipped to $8,600. Lipman knows why. Brokers are busting their orders and putting a surplus of tickets back on the market. The dip, he guesses, is only temporary. Time to buy.

He begins alternating from Blackberry to iPhone at a feverish pace, firing off text instructions to Ayeh and others in his network to buy anything under 10 grand. He starts calling smaller brokers in Phoenix. He wants what they’ve got, and they’re audibly startled to be getting a call from Lipman and not one of his employees.

“I’m freaking them out,” he says, “but it doesn’t matter because we need these tickets. It might already be too late.”

He buys 16 seats for an average of $8,600 during this run, all upper level, and he spends the night plotting how to move them on Sunday morning.

* * *

Lipman at work. (Jed Jacobsohn for The MMQB.)

At 5 a.m. on game day Lipman wakes up, with two hours of sleep, and shaves with a hotel razor, carelessness and fatigue causing tiny cuts all over his cheeks.

The diamond men stay home, but one by one the tickets get plucked off his website, each of them selling for more than $10,000 and the highest for around 12 grand. At noon he’s able to satisfy an MLB owner’s request for a last-minute extra. He fills every order, with the exception of a lower-level order that he has to replace with upper-level tickets.

We make it to the tailgate, under a sponsored tent with a couple hundred attendees and an open bar in the mall parking lot across from the stadium. It’s too big for Lipman’s taste. Not intimate enough. Not how White Glove does things back in Miami. He’s headed back there tonight, and he has no intention of attending the game and getting stuck in Phoenix with all of his customers.

“I like being boutique,” he says. “I’m not trying to be a Ticketmaster behind a desk. This is fun; it’s a real high that you can’t get anywhere else. I want to be so tired after Super Bowl week, I sleep through the whole flight.”

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]