Sweetness and the Scout

Kevin Kelly was 17 years old when he met Walter Payton. It was 1982, and the Bears running back had just finished his seventh NFL season—at age 27 already the fifth-leading rusher in NFL history. Payton was nearing the peak of his celebrity, elusive and powerful on Sundays, and unstoppable in the mind’s eye of 17-year-old boys on varsity football teams in Illinois. Kelly, who played at Barrington High in Chicago’s northwest suburbs, liked to train late at night during the offseason at a local 24-hour health club because the weight room was usually empty at that time. One Friday, Kelly arrived at midnight, scanned the room—and there was Walter Payton.

“He was the only person in the weight room,” Kelly says 32 years later in his home office in Avon, Ind., outside Indianapolis. “And of course, he was my hero. He was every kid’s hero.”

Kelly wondered why Walter Payton would be working out at midnight. He thought, He must be in here because he wants to be alone. So the kid steered clear of the star and began his routine on the other side of the room, while watching Payton out of the corner of his eye.

“After about 30 minutes I could feel him kind of walking across to me,” Kelly says. “So I gathered my stuff, and he’s like ‘Hey, where you going?’

“Look,” Kelly recalls saying, “I’m probably bothering you or something, so I’ll go do something else.”

Payton: “No, no, man. Look, I came over here to see if I can work out with you.”

Kelly: “Okay…”

Payton: “Oh, I’m sorry. I’m Walter Payton.”

* * *

A young Kevin Kelly and Walter Payton. (Courtesy Kevin Kelly)

The story of Kevin Kelly, or rather, what happened next, is about a search. Kelly is but a footnote in Payton’s public legacy—a quote in a newspaper relegated to microfilm; a pair of legs on a television broadcast churning up a steep hill in vain pursuit of a man called Sweetness. And yet for Kelly, Payton became a compass. True north led him to a football life, from Chicago to Miami to Indiana to Cleveland to San Diego, where he’s college scouting director for the Chargers, with the near-impossible mission of finding the next Walter Payton. Kelly would become a friend to Payton, a confidant, a motivator and, late in the Hall of Famer’s life, a shepherd for his only son, Jarrett.

“My dad was a great person for the community in Chicago, but he also had this side where he was very protective of our family,” says Jarrett Payton, an entrepreneur and radio host in Chicago. “The way he let in Kevin Kelly is something incredible that you wouldn’t expect. My dad just felt something about him, and Kevin always had my dad’s back.”

The kinship began that night in the gym. Kelly recalls that Payton really didn’t enjoy heavy lifting (he would later challenge Kelly to explain how the bench press translated to the football field, and if Kelly could convince him, he’d try it out). Instead, he would power-clean 100-pound dumbbells, raising them from the floor to above his head in rapid succession, pumping like engine pistons as if he were ripping away from a tackler. The two ran on the club’s track that night—interval sprints, with Payton bursting around the corners—and they played basketball, one-on-one until 3 a.m.

Afterwards, the two sat in the locker room, dripping with sweat, and a thought rushed to the front of Kelly’s mind.

Nobody is going to believe me. I don’t even have his autograph!

So he walked to the sink where Payton was fixing his hair and pretended to occupy himself, unsure of what to say. Then Payton said, “Hey, wanna go grab a beer?”

After the drink, Payton wrote his phone number down on a napkin and handed it over. “You want to do this again?”

“Yes,” Kelly said, though his more immediate concern was that he'd broken his parents’ curfew by three hours that night. “I’ll call you tomorrow.”

Payton: “No you won’t. You’ll be too sore. I won’t see you again.”

Kelly: “You met the wrong guy tonight. I’m coming back.”

* * *

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3-nVzGHoOXc?rel=0]

Above: A clip from a Bears-Falcons telecast in 1984 showing Walter Payton and Kevin Kelly, then in college, running the hill in Arlington Heights. Because of camera difficulties at the time of filming, only their backs were seen on screen.

The hill was set on a landfill in Arlington Heights, Ill. In summers, the Bears back would sprint up the steep incline again and again, rep after rep—a grueling workout that would burn out lesser men and helped burnish the legend of Walter Payton. To Kelly, who would often join him in those hill sessions, the experience was unforgettable—especially the smell. “It was just bad,” he says. “You’d have to go to a garbage dump to smell anything like that.”

There were lessons on that hill. Shards of glass and chunks of plastic jutted up from the ground. The odor was only bearable at the summit. Once, Kelly pleaded with Payton: “This place sucks! Can we go train somewhere else?”

“He looked at me just brutally,” Kelly says, “just stone dead, and he was like, ‘Look, if I could make it harder, I would make it harder. I’m not trying to make it easier around here.’ ”

Kelly learned how to run by chasing Payton, who lived life on the balls of his feet, the imprint of his heel never making a track in the dirt. They ran at Payton’s whim, and not just the hill. Payton would occasionally get the itch in the middle of an offseason sponsor dinner or magazine photoshoot.

Says Kelly: “He’d be like, ‘Hey, look—we gotta go. Go start the car, we’re out of here.’ ”

In the forest preserve, Kelly says, “He’d dodge trees like they were tacklers. I mean, full-speed—branches would be flying.”

And they’d go running, no matter the hour. The track at the health club and the track at Barrington High were favorites. One summer Payton met a farmer with a large property beyond the north suburbs and asked the man if they could train with his four-foot-high hay bales. The bales were ordered in straight lines at 20-yard intervals for a mile. The first time, Kelly and Payton got in front of their respective rows and Payton said, “Get over it any way you can. Just get to the next one.”

Kelly could vault the first 10 or so by planting one cleat in the front of the bale and jumping over. For the rest he could only sprint around them. Meanwhile, Payton was clearing them as if they were track hurdles. Sometimes he leapt head-first over the bale and rolled to his feet, à la his signature goal-line dive.

“People would say, ‘Oh, it’s so dangerous when he hurdles the goal line,’ ” Kelly says, “and I would laugh because he would do it with no pads and just land on the back of his shoulders.”

There was a nearby forest preserve full of pine trees, and Payton figured he could train his body for punishment and his vision for open lanes if he held a football and sprinted through the woods, avoiding the obstacles he couldn’t run through. Kelly trailed behind, slowly navigating the brush.

“He would run through there and dodge the trees like they were tacklers,” Kelly says. “I mean, full-speed—branches would be flying. I think in the six or seven summers, twice he ran smack into a tree and both times I was like, Oh my God!

“He’d go down, then get up and pat himself on his arms and shoulders and say, ‘I’m fine.’ He was just unstoppable.”

* * *

Sweetness and the Scout

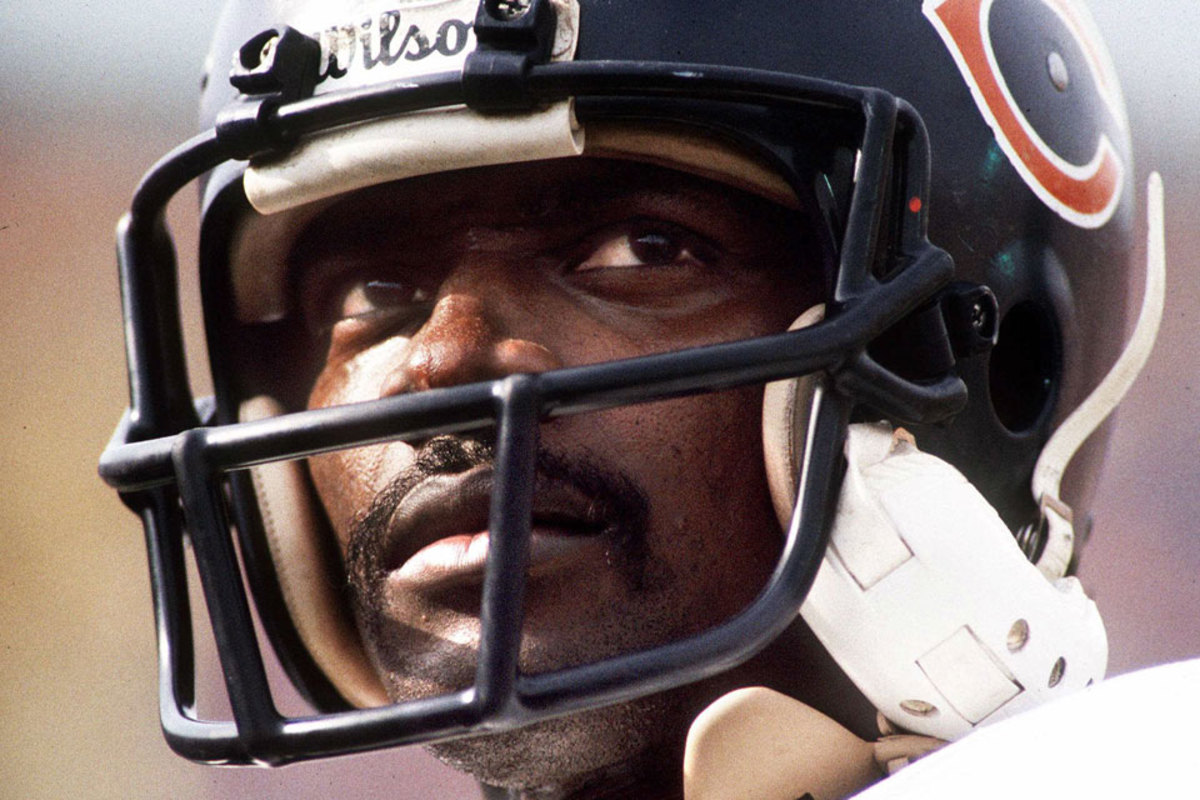

Payton goes up and over in 1984. (Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated)

Payton goes up and over in 1984. (Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated)

Payton goes up and over in 1984. (Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated)

Payton goes up and over in 1984. (Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated)

Payton goes up and over in 1984. (Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated)

When Kelly graduated from Barrington High in ’83, he had a choice between accepting one of the small-school scholarship offers he’d received as a 5-9 linebacker or attending the University of Miami to major in business, and walking on to the football team. “I figured I’d have a shot,” Kelly says. “I didn’t know I was walking on to the best football team in America.”

Kelly’s fellow freshmen included Alonzo Highsmith and Jerome Brown, respectively the eventual No. 3 and 9 picks in the 1987 draft. The scout team defense included Danny Stubbs and Winston Moss. The scout team quarterback was Vinny Testaverde. More than a third of the roster wound up playing in the NFL.

“It was overwhelming how good these guys were,” Kelly says. “I was awestruck. I was trying to make a team, and it wasn’t going great.”

As a non-scholarship athlete, Kelly was placed in a regular dorm, which meant he was the only inhabitant of his floor when summer practices began. One night after midnight the phone in the hallway started ringing, over and over again.

“Finally I went and got it, and it was him”—Payton—“and he was like, ‘What the hell? You leave and you don’t call?’ And I’m like, ‘Look, bro, I’m struggling, and I don’t feel like dumping it on anybody. I’m just trying to make my way.’ ”

Payton: “What’s the problem?”

Kelly: “These guys are damn good down here.”

Payton: “You think I’m pretty good, right?”

Kelly: “Come on, you’re the best.”

Payton: “Alright, you tackle me in the summertime. What you sweating about now?”

It hit Kelly that night on the phone in Miami—those daily brushes with pure relentlessness. He didn’t know if he could match that intensity, but he knew what it looked like.

* * *

Jarrett and Walter in February 1999. (Steve Liss/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

In the late ’90s, Payton’s celebrity in Illinois was so large he had to sneak into his son’s high school football games and watch from on top of the press box to avoid being mobbed by fans. The coach of that St. Viator High team was Kevin Kelly.

After earning a national championship ring with Miami in ’83, Kelly had transferred to Indiana in search of more playing time and as a senior was a captain for the Hoosiers’ ’87 Peach Bowl team. After graduating he had assistant coaching stints at Indiana, Lake Forest College, John Carroll University and Case Western before taking the head coaching job at St. Viator. Upon his arrival, Payton visited his cramped new office and wrote the number 4 on a whiteboard.

“I’m just telling you,” Payton said, “you get a play, and every time you call that play you get four yards, and you’re going to win.”

The year after Kelly arrived at St. Viator, Jarrett, who had played soccer through his sophomore year, switched to football to be Kelly’s quarterback. Payton had a request for the coach: Help Jarrett discover the work ethic I’ve taught you. Together Kelly and Jarrett found their four-yard play—a quarterback sweep. Then, in Jarrett’s senior year, the team’s starting running back went down with an injury, and Kelly asked Jarrett to switch positions.

“Kevin would never pat me on the back and say, Good job,” Jarrett says. “It was always, You can do better. I was upset when he asked me to move to running back, because I was just learning quarterback. And he said, You have to adjust. That’s the game of football. And that’s how life goes. It’s never goes the way it’s scripted.”

Payton had a request for Kelly: Help Jarrett discover the work ethic I’ve taught you.

St. Viator won the 1998 conference title on the strength of more than 2,800 all-purpose yards from Jarrett, who was named Illinois player of the year. The following January he held a press conference to announce his school of choice. At that point America didn’t know of the physical and mental anguish his father was in. Secretly, Walter was being destroyed by a rare liver disorder. He’d visited the Mayo Clinic in Rochester and had exploratory surgery, with no success. Payton, who had never fluctuated more than five pounds his entire career, was a waif. “It went fast, and he tried to stay out of the limelight,” Kelly says.

Kelly asked Payton to stay home for his son’s announcement rather than face reporters alongside his Jarrett and ignite suspicion as to his well-being. “You know damn well he was like, ‘No, I gotta be there for my son,’ ” Kelly says. “It was impossible to stop him once he made his mind up.”

Walter died less than a year later, on Nov. 1, 1999. Kelly tried to relay to Jarrett, then a freshman at Miami, some of the spirit he’d learned from Walter. “Listen, bro,” Kelly told him. “Your dad’s football flame fuels me. Don’t let it bring you down. Let it fuel you.”

Kelly’s first son was born a few months later. As a kid in central Indiana, Payton Kelly asked his father why his name wasn’t spelled with an e, like that of the Colts’ quarterback. Dad gritted his teeth and sat his son down to watch highlights of his old friend, and to tell the story.

“Kevin’s son and my son and my dad have these similarities,” Jarrett says. “I believe that when people are taken from us too soon, there’s someone being born with those same traits, carrying it forward. The quality of being hardheaded, and the kindness.”

The stories of Walter Payton’s single-mindedness are legion. Kelly knew him to wear a pair of leather shoulder pads from his college days long after the NFL converted to plastic. He recalls stumbling upon Payton’s equipment bag lying on the ground inside the gun range within Payton’s mansion after his retirement. In the bag he found those same beaten pads and an old Bears helmet with primitive cloth suspension, the kind worn in the ’60s.

“It just looked like kiddie equipment,” Kelly says.

If these were in his gun range, Kelly wondered, whose pads were sitting in the Hall of Fame?

“He said they just sent off some pair of pads that always sat in his locker, but he never wore them,” Kelly says.

* * *

Kevin Kelly (center, sunglasses) and Chargers staff. (Courtesy San Diego Chargers)

Payton played through injuries of every kind, missing one game in his rookie season with a shoulder injury, then playing in 186 consecutive games until retirement. And he was quick to remind anyone who brought it up that he was forced to sit out that one game by the Bears’ trainers. That’s the kind of athlete Kelly is looking for as the Chargers’ scouting director.

“Is this guy a warrior?” says Kelly, who moved from high school coaching to NFL scouting in 2001 and worked for the Browns, Colts and Jets before joining San Diego’s staff. “Is this guy tough-minded? Is he really a team guy? Is he a self-starter? You’re looking for qualities that outweigh something on your stopwatch.”

Scouts have a well-worn axiom for intangible qualities: If you have to look hard, it’s probably not there. Says Kelly: “We’re after those things, and they’re really hard to find, but if you just hang your hat on those intangibles, a lot of the time they work out.”

A few of Kelly’s hits over the years, according to three NFL personnel men who have worked closely with him: In 2003, as a Browns scout, he pushed hard for the franchise to take Tony Romo out of Eastern Illinois, who went undrafted and landed in Dallas. In 2005 with Cleveland, Kelly was instrumental in identifying Kent State quarterback Josh Cribbs as a priority undrafted free agent. (Cribbs would make two All Pro teams as a return specialist.) In 2010 with Indianapolis, Kelly was high on Central Michigan receiver Antonio Brown, who ultimately went to the Steelers in the sixth round and had 129 receptions in 2014, the second-highest single-season total in history. In 2013 he pushed for the Jets to draft defensive end Sheldon Richardson out of Missouri with the 13thpick. They did, and Richardson was the 2013 defensive rookie of the year.

“He’s very thorough, sees the whole picture, loves the job,” former Colts general manager Bill Polian says of Kelly, “and he works at it night and day. And on top of that he has an innate ability to recognize talent and where talent fits.”

Every year, Polian says, he’d ask Kelly who his guys were in the upcoming draft. Almost invariably, those guys would make it somewhere.

“Whenever I think about reports or making decisions surrounding players, I think of Walter often,” Kelly says. “He was the mold you’re looking for.”

In the decade and a half since Payton’s death, that same ambition that Kelly has been chasing for a decade—and which Jarrett sees in Kelly’s son—has put the final shadowy chapter of Payton’s life into perspective.

* * *

Walter Payton in February 1999. (David Walberg for Sports Illustrated)

While outwardly maintaining his buoyant public persona, Payton in retirement was constantly in search of direction and purpose, veering from one pursuit to the next. Quietly separated from his wife, he tried his hand at television, auto racing and restaurants. Like many players, he continued to use painkillers after his playing days were over. As detailed in the final chapters of Jeff Pearlman’s 2011 biography Sweetness, he also suffered from depression and told people of suicidal thoughts. His greatest post-career ambition—one that might have offered him some semblance of the professional fulfillment he got on the football field—was to own an NFL team, but that quest was derailed by dissension among a group of investors (including Payton) that tried to bring an expansion franchise to St. Louis in 1995. Jacksonville and Charlotte got the new teams that year, and St. Louis got the Rams from Los Angeles. Payton aspired to be team president in addition to co-owner, and Kelly would have had a coaching role.

“Walter struggled with retirement, just like I struggled hanging it up at 21,” says Kelly. “He was finding his way, and I think those are difficult things for most NFL players.”

Upon years of reflection, amid a growing national awareness of the effect of head trauma in football, Kelly has wondered whether Payton’s physical approach to the game might be a clue to his later behavior. “His running style was so rugged,” Kelly says. "I mean, he wasn’t going out of bounds with anybody. Knowing what we know now about the brain—he really was a different guy in the end. Part of me wishes to know, but we’ll just never know.… It would be shocking to me if it wasn’t a factor.”

Kelly often thinks of his days under Payton’s tutelage but doesn’t speak about it very much. He’s not interested in writing a book, and he never even dared tell his college teammates that he spent his summers training with Sweetness, because he knew they wouldn’t believe him. But above his desk at his house in Indiana hangs a portrait of that hill back in Illinois. While Kelly was coaching Jarrett in high school, the hill was bulldozed and manicured to become part of a par-3 golf course. Walter had a photograph taken and sent the picture to Kelly as a gift.

Says Kelly: “It represents to me what we’re looking for.”

* * *

(Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

Before the NFL scouting jobs and the championship at St. Viator, before Indiana and Miami, and even before the hill, there was one unlikely night that set a kinship in motion. A 17-year-old arrived home at 4 a.m. to find his father up and reading the morning paper. The son explained that he’d met Walter Payton and worked out with him for three hours, and the two had then had a beer. He showed his father the napkin with Payton’s name and phone number. Kelly’s dad grounded Kevin indefinitely.

That afternoon Kevin called Walter to tell him the bad news.

“Hey Walter, it’s Kevin. Do you remember me?”

“Sure. Are you coming to work out?”

“No, I can’t. I busted curfew. I got in some trouble”

“Oh s---. Do you think if I came over I could fix it?”

“Yeah, I believe you could.”

So that evening, while Mr. and Mrs. Kelly and their three sons were sitting down to dinner, Walter Payton arrived at the front door, in the flesh.

Mr. Kelly, I need your son to help me work out.

“I think my dad choked on his pork chop,” Kelly says.

“There are just so many stories, what that guy did for me and my family. They’re endless.”

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]