Antonio Gates Will Retire with a Ring

DETROIT — Last Friday was fight night in the Motor City, and the crowd of nearly 500 rumbled alive nine minutes past midnight as Ronnie “Teflon Ron” Austion sauntered into the dimly lit arena.

A 20-year-old welterweight and hometown favorite, Teflon Ron wore a red satin cape trimmed with white fur—a flair he dreamed up around Christmastime—and strode down the aisle flanked by a 17-member entourage that included a teenager rapping on a wireless microphone and a few children who got caught up in the whirlwind. “I don’t even know who half those people were,” he’d later say.

• Also on The MMQB: After a turbulent final act with the Jets, Rex Ryan is starting fresh in Buffalo

Hooting and hollering, the spectators all but abandoned their $7.50 well drinks and $1.75 bags of Doritos by the time Teflon Ron entered the ring at Detroit’s Masonic Temple. The building is a 14-story cathedral that houses three theaters, a bowling alley and an Olympic-sized swimming pool (unfilled). The walls are wood-paneled and the fraying carpets are adorned with paisley designs, suggesting they haven’t been replaced in decades. But Teflon Ron didn’t notice the finer details of neglect. His focused was trained on Memphis fighter Dedrick Bell, the other half of the night’s headliner bout.

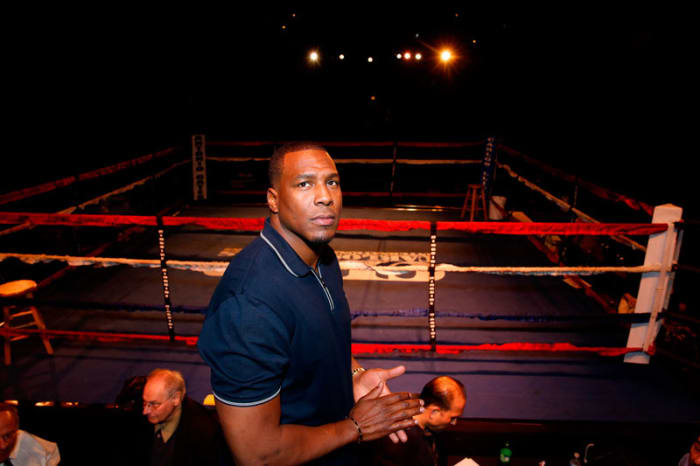

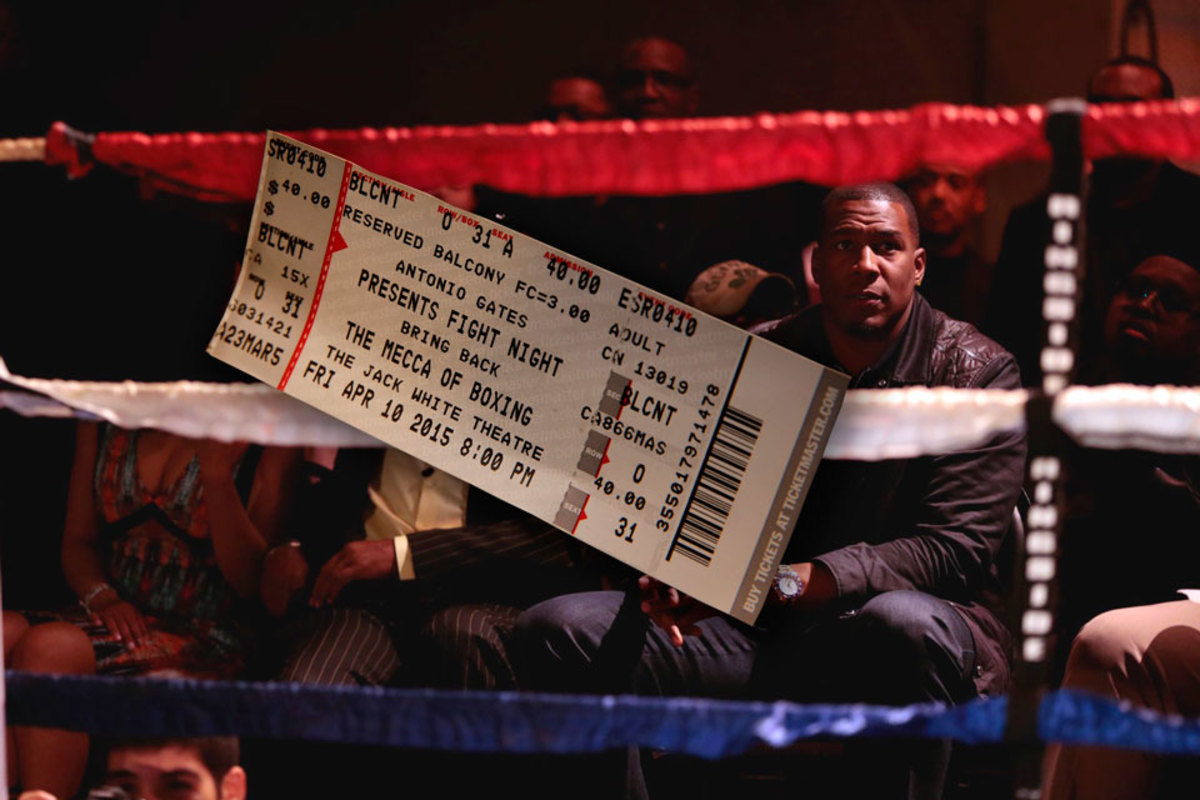

Amped up from a day of solitude and a Naked Green Machine smoothie he chugged three hours earlier, he jogged around the canvas, stopping only to acknowledge a hulking man sitting ringside in dark jeans a black shirt. People approached this man all night to shake his hand, whisper in his ear and unapologetically demand selfies. He is Teflon Ron’s promoter, mentor, and the boxing show’s financial backer. Everyone knows him as Antonio Gates, tight end for the San Diego Chargers.

* * *

Antonio Gates Will Retire with a Ring

After eight rounds, Ronnie Austion (l.) won an unanimous decision over Dedrick Bell of Memphis. (Jeffrey Kowalsky for The MMQB)

Antonio Gates’ great grandfather was a pro boxer in Detroit, and he grew up idolizing fighters such as Tommy Hearns. (Jeffrey Kowalsky for The MMQB)

Hearns, the Motor City Cobra, working out at Kronk Gym in 1980, and sitting ringside at last Friday’s fights promoted by Gates. (Paul Kennedy for Sports Illustrated :: Jeffrey Kowalsky for The MMQB)

Gates began promoting boxing matches in 2013, setting himself up for life after football while giving back to his hometown. (Jeffrey Kowalsky for The MMQB)

Gates hasn’t yet retired to the sideline, but the soon-to-be 35-year-old is in the twilight of his NFL career. When Dwight Freeney became a free agent this offseason, Gates not only inherited the title of Oldest Charger, he also had an unsettling epiphany: Most players in the 2015 draft class were still in diapers when he was in high school.

On the cusp of his 13th season, Gates has only one year remaining on his contract and is acutely aware of his expiring clock. He no longer attends voluntary workouts, nor has he done any route running this offseason.

“With injuries and whatnot, I played a little bit more than they expected me to play last season,” he says. “I was playing the whole game. How I feel next year, it depends on how much volume they have me doing. I’d like to come in on third-and-7s, red zones, those situations. That’s what my contribution is at anyway.”

Gates has been thinking about his farewell moment since running back LaDainian Tomlinson, his former teammate and good friend, retired in 2012. This winter, center Nick Hardwick said goodbye after 11 seasons, forcing Gates to ponder how he’ll leave the game. Will he play it cool or will tears stream down his face when the Chargers hold a press conference to eulogize his career?

“It could be one year for me, it could be four years, I don’t know,” he says. “I just wonder how I’ll handle it.”

“Growing up in Detroit isn’t always easy,” Gates says. “That’s why I’m doing this. If I can get one kid off the streets, or help one kid start his career, or have a role in one kid becoming a man, then it’s worth it.”

Despite his current contract including $20.4 million in guarantees and despite living in a Hollywood mansion so luxurious that it was once featured on a Bravo reality show, Gates is haunted by what he calls the countless “horror stories” of life after the NFL. He doesn’t want to become one of those guys who hangs up the cleats and falls into a depression or depletes his bank account.

“You’ve been competing and traveling for so many years,” he says. “Then all of the sudden you’re going to be sitting at home and feel like you’re not yourself. You’ll feel like you’re not contributing to football, or to life. I don’t want to have that feeling. I’m terrified of having that feeling.”

It’s why he’s sitting ringside in Detroit on a Friday night in early April, watching Teflon Ron establish dominance after four rounds of chasing his opponent with incessant jabs. Hunched in his seat, Gates often taps his right leg nervously and shouts, “C’mon Ronnie!” Known for flash and power, Teflon Ron is forced to chip away with body shots in order to earn a unanimous decision. Gates stands and cheers at the announcement, clapping thunderously.

“He cares about each of us,” says Robert O’Quinn, a 21-year-old from Detroit and one of the five fighters on Gates’ roster. “He cares about this city.”

* * *

Antonio Gates Will Retire with a Ring

Through 12 seasons, Gates has caught 788 passes for 10,014 yards and 99 touchdowns—all franchise records in San Diego. (John W. McDonough for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

(John W. McDonough for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

(John W. McDonough for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

(John W. McDonough for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

(Al Tielemans for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Gates relaxing in his pool during a 2007 SI photo shoot. (Robert Beck for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Antonio Gates’ unconventional road to an eight-time Pro Bowl career has become NFL folklore. He was a standout football and basketball player at Central High in Detroit, where he won a Michigan state hoops title, and he led Kent State to the Elite Eight in 2002. At just 6’ 4”, his NBA future was uncertain. But countless NFL scouts contacted him about trying out despite his never having played a down of college football.

Few people know about Gates’ connections to Detroit’s boxing scene. His great grandfather was a pro fighter, and growing up he loved watching guys such as Tommy Hearns, the Motor City Cobra, who sat ringside for Gates’ eight-bout card. Gates often trained in the city’s gyms, where he earned praise for his quick hands and powerful punch. Though he moved on to other sports and eventually across the country, he always kept tabs on the goings on back home.

When Detroit’s legendary trainer Emmanuel Steward passed away in 2012, the local boxing landscape crumbled. Young fighters started getting bad advice from a cadre of dodgy promoters, and fewer and fewer shows were being organized. A year later, Gates got his promotional and managing licenses in order to launch AG Promotions, which has now staged three events. His purpose is two-fold: to run a business he can jump into full-time when his NFL days are over, and to give back to his community.

“How I feel next year, it depends on how much volume they have me doing,” Gates says of the 2015 season. “I’d like to come in on third-and-7s, red zones, those situations.”

“Growing up in Detroit isn’t always easy,” says Gates, who is planning to open his own gym in the near future. “I know what it’s like to want to be somebody, and I know what it’s like to become somebody. That’s why I’m doing this. If I can get one kid off the streets, or help one kid start his career, or have a role in one kid becoming a man, then it’s worth it.”

Earnest intentions and a famous name will only get you so far in the world of boxing. Gates’ cousin, Tony Harrison, is one of Detroit’s top prospects. But he’s managed by Vegas-based promoter Al Haymon, who arranged for Harrison’s April 17 bout to be televised on ESPN. So far Gates has poured tens of thousands of his own money into each of his three shows—none of them televised—and it may take him a few years until he starts turning a profit.

“We’ve had so many promoters come in and say they can propel a comeback,” says Stuart Kirschenbaum, Michigan's boxing commissioner from 1981 to 1992. “What they inevitably find is that it’s very hard to make money doing this. They learn lessons the hard way.”

“A lot of people want to see a quick turnaround, and want to see results. There are also doubters who say I should spend my money elsewhere,” Gates says. “You’re not necessarily happy with it on the business side, but I get satisfaction in other ways.”

* * *

Ronnie Austion (l.) and Antonio Gates (Jeffrey Kowalsky for The MMQB)

It’s Saturday afternoon, and Teflon Ron has simply become Ronnie Austion again. Wearing a white polo shirt and black skinny jeans, he strolls into a private room in a pricy seafood restaurant to meet Gates. His eyes light up as he slides into a chair next to his mentor.

“How you feeling?” Gates asks, inspecting the fighter’s hands.

“Like I want to eat everything on the menu at White Castle,” Austion says, grinning.

He explains how Bell was different than he had looked on film; his stance was wide and a bit awkward, making him harder to hit. The fight turned into a defensive standoff.

“My legs are just a little sore,” says Austion, who is now 9-0, with six knockouts.

Gates nods. “I know how that is,” he says.

Through 12 seasons, Gates has caught 788 passes for 10,014 yards and 99 touchdowns—all franchise records in San Diego. Among tight ends in NFL history, he ranks fourth in catches and yards, and second in TDs. He’s caught 549 passes for first downs—second only to Tony Gonzalez—and his 80 catches of 25 yards or more are the most by anyone to ever play his position. He posted those numbers while sharing an offense with LaDainian Tomlinson for nine seasons, during which time Tomlinson led the NFL in rushing yards, carries and TDs.

Gates is putting the finishing touches on a likely Hall of Fame career, but he still remembers the unnerving feeling of moving to San Diego as an undrafted free agent. He tells his fighters stories about how he sometimes cried himself to sleep because he hadn’t seen his family in months, and about how he had to cut off some friends from Detroit in order to avoid distractions as he found his way.

“These were things I had to learn as a pro,” Gates says. “Maybe it helps them become champions, maybe not. But it will help them become better men.”

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]