A Marshawn Kind of Way

PHILADELPHIA — Marshawn Lynch must have taken the quickest shower in NFL history, or maybe he didn’t even shower at all. Either way, he was dressed and on his way out of the visitors’ locker room just minutes after his bruising 86-yard performance in the Seahawks’ 24-14 win over the Eagles on Sunday.

He stopped shy of the exit to grab Richard Sherman by his shoulder pads, playfully pushing and pulling and heaping praise on the taller cornerback.

“You a beast!” he shouted. “I want to be like you when I grow up!”

“No,” Sherman said, grinning. “You are.”

Lynch let go and headed for the door. Approached by a lone reporter, he spun around and stared back with dead eyes from under the hood of his jacket. His isn’t a thousand-yard stare; it’s an ice-cold glare. The way Lynch looks at men who want something from him but know nothing about him should be preserved and catalogued in the name of behavioral science. He’ll listen to your pitch, but his mind is already made up.

A Marshawn Kind of Way

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Bill Frakes/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

John Biever/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

To understand Marshawn Lynch’s current status in Seattle, amid reports that his standing is diminished within the organization, you have to go back more than four years to when he was traded from Buffalo.

Lynch became a Seahawk in early October 2010, and his first team meeting set the tone for what would become a three-season odyssey that included a Super Bowl victory last February. Pete Carroll asked him to stand. The head coach then told Lynch that during training camp that year, while Lynch was still in Buffalo, each member of the Seahawks shared a story about the worst thing that ever happened to him.

“It’s the only way we’re going to be a team,” Carroll said, according to two players who were in the room.

Lynch, who some friends believe has a fear of public speaking, looked around and saw solemn faces and nodding heads. An assistant coach in the back of the room shouted, “It’s a safe place, man!”

Lynch, who grew up with three siblings and a single mother in Oakland, started to tell as heartfelt a tale as any new Seahawk before him. But he couldn’t get the first sentence out before Carroll and others interrupted.

“Sit down!” they yelled. “Nobody cares about your sob story!”

At first incredulous, Lynch quickly got the joke and smiled. Then Carroll addressed him again, this time sincerely.

“Marshawn, people have been trying to change you your whole life,” Carroll said, according to the same two players. “They’re trying to make you into something you’re not. Here are the things that are important to us—our three rules—other than that, I have a ton of respect for you and I want you to be you.”

The rules that Carroll relayed:

Number 1. Protect the team: At practice realize you’re going up against your own guys. Or when you’re out drinking it’s your responsibility to take his keys away and find him a way home, almost more than it is his.

Number 2. No whining. No excuses. No complaining.

Number 3. Be early. It’s a sign of respect.

And so began Marshawn Lynch’s second chance.

(Al Tielemans/SI/The MMQB)

He has always been a one-of-a-kind runner. “There were very few like him that I’ve ever seen,” says Dick Jauron, the coach who drafted him in Buffalo. “He was just relentless in getting north and south and getting to that goal line.” And though he had rushed for more than 1,000 yards in each of his first two seasons with the Bills, Lynch, the 12th pick in the ’07 draft, soon was viewed as expendable.

Lynch pleaded guilty to a hit-and-run charge after striking a pedestrian in 2008 in Buffalo, and in 2009 he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor weapons charge stemming from an offseason arrest in California. There were other, unpublicized run-ins that people close to Lynch characterize as profiling. His condo association busted him for having a dog, even though other tenants had dogs. And he was pulled over and cited for playing music too loudly—not on the street, but in the Bills’ stadium parking lot.

“When the legal stuff came up,” Jauron says, “I needed to know how it happened, what he felt, what he was thinking. He never tried to pull the wool over my eyes. He would willingly admit errors and move on with his life.”

Jauron, who still adores Lynch personally and professionally, was fired by the Bills in November 2009, and the new regime made a business decision to trade Lynch to Seattle.

It was around this time that Lynch largely stopped engaging with the media. He had his favorites, including Mike Silver, and he let Sports Illustrated write about his personal life on a 2012 charity trip to Oakland, but for the most part he shut down. “As you know, he’s not the easiest interview,” Jauron says. “Once he’s comfortable he’s easy to be around. But like a lot of people he’s not going to offer a lot about himself until he really trusts you, and even then he’s just not much of a talker about himself.” The Seahawks didn’t expect him to do anything but be a good teammate and produce on the field. Carroll would tell him, “Make the main thing the main thing.”

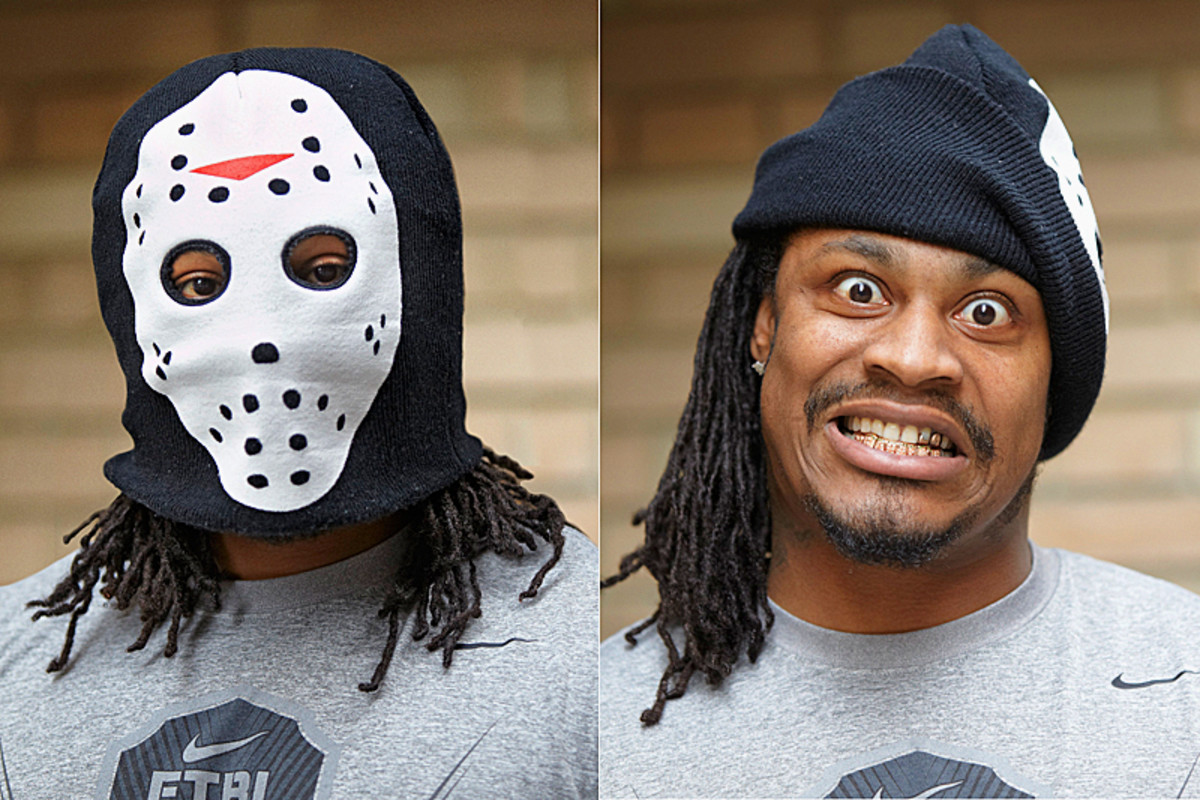

In the absence of his words, however, perception and observation began to dictate the narrative. His long hair and gold teeth spoke for him.

Lynch is quiet.

Lynch is ornery.

Lynch is a thug.

And, most recently, Lynch is a jerk because he won’t talk to the media.

“I think race plays a role in how he is perceived,” says ESPN’s Kenny Mayne, who did a celebrated TV spot with Lynch during his rookie season, visiting Buffalo’s fine-dining establishments such as Applebee’s. “There’s something about the background that influences conversation. If he was a white country boy with long hair and a happy-go-lucky attitude, but wouldn’t talk to media, he’d be one of the NFL’s great characters. But he won’t talk and he blasts that rap music, which probably scares some people off.”

Many players support Lynch’s stance. Some even envy it.

“There are days when I don’t feel like dealing with media,” says Ravens wide receiver Steve Smith, a friend of Lynch’s. “People think he’s hiding something because he doesn’t want to talk. He does his job and does it well, and he’s not interested in other things. There are people who use the media to give false perceptions of who they are. He’s not interested in any of that. He just wants to ball.”

And yet, Lynch really is hiding something: A series of kind acts that he would prefer to keep secret.

A Marshawn Kind of Way

Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Deanne Fitzmaurice for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Deanne Fitzmaurice for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Deanne Fitzmaurice for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

During his college years at Cal, if a teammate, friend or acquaintance complimented Lynch on the shirt he was wearing, he would hand it over. “He’s walking around on the street with his shirt off,” says Ravens running back Justin Forsett, a former teammate of Lynch's at Cal and in Seattle. “Just because somebody said, ‘That’s a nice shirt.’ ”

When Lynch was a sophomore, he struck up a conversation with Nick Sundberg, a freshman, one day as they stretched near each other. “I was intimidated by everybody because I was 17, I had no idea what to expect about college,” says Sundberg, who has played for Washington since 2010. “I just stayed quiet, but he asked me where I was from, got to know me. He would do that with other freshman. He did that with me, and I was just a long snapper.

“We were at a banquet during his junior year, and my mom ran into him in the hallway on her way to the bathroom. And she came back 20 minutes later and she was like, ‘I met Marshawn and he was the nicest boy!’

“To this day her favorite NFL player is me. And her second favorite is Marshawn Lynch.”

By his junior season, Lynch had rushed for nearly 2,000 yards, with 18 touchdowns, and was a Heisman candidate. The school launched a website promoting his bid: Marshawn10.com. But Lynch wasn’t interested. A national magazine went to Cal to profile him, but Lynch begged off the interview and put his cousin, wide receiver Robert Jordan, in front of the reporter instead. During games he would feign exhaustion and take himself out so Forsett, his backup, could get snaps.

“He did that almost every game at Cal, and even when we both played in Seattle,” Forsett says. “I’m sure the coaches weren’t too pleased. But it wasn’t that blatant. They would think, OK, he needs a rest, but he never did.

“If it wasn’t for him taking himself out of games and allowing me to go in and play, I probably wouldn’t have gotten the opportunity.”

When Lynch picked an agent, Doug Hendrickson out of the Bay Area, his initial questions surprised the veteran negotiator.

“In the first meeting, he wasn’t asking about his contract, marketing money,” Hendrickson says. “Honest to God his dream was to build a youth center for kids in Oakland, and today we’re near accomplishing that goal [with his Fam 1st Family Foundation].”

Lynch, 28, made lasting relationships during his Buffalo days. During Super Bowl week last February, the peak of Lynch’s dissonance with local and national media, he called Shone Gipson, a Bills assistant athletic trainer, to offer condolences on the death of his father. “For him to do that, with everything he had going on,” Gipson says, “it meant a lot to me, and it showed a lot about who he is.”

Before Jauron’s daughter, Amy, married Falcons media relations assistant Brian Cearns in 2012, Lynch called his buddies who played for Atlanta, including former Pro Bowl safety Lawyer Milloy, to make sure Cearns was an upstanding guy. Apparently satisfied, he never told Jauron that he'd vetted the coach’s future son-in-law.

“That’s priceless,” Jauron said upon being told the news more than two years later. “That’s Marshawn.”

In Seattle, on Fridays preceding a home game, Lynch plucks a kid from an impoverished background from the city and brings him and his family to the Seahawks’ practice facility. Lynch, who isn’t married and doesn’t have kids, shows his guests around the locker room and introduces them to coaches. He won’t allow the team’s media relations staff to invite a news outlet to witness or write about his interactions with fans.

“He kind of started his own Make a Wish thing,” linebacker Malcolm Smith says.

“He does things outside of the media that no one ever sees,” says linebacker K.J. Wright, “and most guys do it to get on TV. But he does it from the heart. It’s real.”

More than half of the former teammates The MMQB tried to interview for this story declined. Others were vague in their answers. Most were reticent to speak about a player who has become a perceived enemy of the working press. Others preferred to mirror Marshawn’s policy on privacy. Former Bills running backs coach Eric Studesville, now with Denver, was “appreciative of interest,” wrote a Broncos spokesman, “but elected to keep things private for now.” Former player Michael Robinson, who landed a fluffy interview with his friend and former teammate that aired on NFL Network on Sunday, didn’t return phone correspondence.

Others, however, were happy to share good words.

During the Seahawks’ visit to Carolina this season, Lynch somehow got a ride 25 miles outside of Charlotte just to visit the family of former Seahawks running back Leon Washington, who was at work with the Titans. “One of the best teammates I’ve ever had,” Washington says.

Says Jauron: “One of the best teammates I’ve ever seen.”

Says Sundberg: “One of the nicest guys I’ve ever played with.”

Says Malcolm Smith: “The best teammate I’ve ever had.”

“He only trusts a select few people,” says K.J. Wright, “and I’m just happy to be one of the guys he trusts.”

(Donald Miralle for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

That Marshawn is a private person with a distinctive personality and an atypical agenda is well documented. The question of why remains a bit of a mystery, and his current standing in Seattle remains up for debate.

During a rare interview, with ESPN’s Jeffrey Chadiha in 2013, Lynch grew emotional in response to the suggestion that his early legal troubles indicated his true colors.

“I would like to see them [critics] grow up in project housing authorities, being racially profiled growing up, sometimes not even having nothing to eat, sometimes having to wear the same damn clothes to school for a whole week,” Lynch said, tearing up. “Then all of a sudden a big-ass change in their life, like their dream come true, to the point they’re starting their career, at 20 years old, when they still don’t know [expletive]. I would like to see some of the mistakes they would make.”

It was one of the rare instances in which Lynch delved into his childhood. In the 2012 SI story, he described growing up in Oakland and walking the streets with his cousin. “We'd walk seven blocks from Josh's house to my house, and you'd never know what was going to happen,” he said. “You could see a shootout; you could see somebody dealing drugs; you could be stopped by the police; you could see hookers. We saw a lotta s--- kids ain't supposed to see.”

“When you grow up a certain way, and certain things happen to you, it shapes you,” Washington says. “He’s learning how to deal with that.”

Sherman says the work with Oakland’s youth provides a sort of redemption for what Marshawn lost in childhood; an opportunity to fill a personal void.

“He sees himself in those kids,” Sherman says, “but he doesn’t like a lot of adults all that much. It’s mostly a trust thing. He’s been kind of screwed over, then being depicted as a bad guy, a thug, but he’s really a smart guy. He just doesn’t have much to say.”

The other school of thought on Marshawn Lynch is that he loathes drawing attention to himself. He’d rather put the spotlight elsewhere.

“My perception is that he doesn’t want it to be about him,” Forsett says. “It’s about others. And he shouldn’t have to make it about him if he doesn’t want to.”

But if that were true, how do you explain the scene after the Super Bowl, with Lynch blasting rap music at such a high volume that any sort of interview with his media-savvy teammates had to be conducted outside the locker room? Same for his Skittles endorsement and other TV spots that put Lynch in the spotlight. He put himself in the public arena for profit, trademarking the phrase “Beast Mode.” And how do you justify all the attention Lynch brings upon himself by refusing to talk, earning fines up to $100,000 for what the NFL considers a job requirement? Not showing up to the White House celebration did the opposite of putting the focus on his teammates. The headline became, Where’s Marshawn?

If Lynch were truly so selfless, why wouldn’t he take that $100,000 and save it for charity, rather than owe it to the NFL in an easily avoidable fine? Plenty of athletes and coaches fulfill their media obligations with vague, clichéd responses that amount to nothing. Why can’t Lynch just do the same?

(Rod Mar for SI/The MMQB)

“I think it’s two things,” says former Seahawks teammate Matt Hasselbeck. “He’s an introvert, but he doesn’t want to conform. What made Seattle perfect, and allowed him to flourish, was the fact that Pete Carroll never made him conform. Pete never gave him a dress code. Him talking to the media was not treated like part of the main thing. It’s a set of rules somebody at Park Avenue came up with, and they mean nothing to him.”

The environment in Renton, Wash., nurtured Lynch’s inclination to reject those who could possibly put words in his mouth. He became the owner of his message, and the earning power that came with it. He’d prefer not to talk, but if the league is going to fine him for not doing so, how better to recoup that money than to use his mysterious public persona as a marketing tool, at the same time sticking it to the league? (The NFL did not respond to The MMQB’s request for comment on the possibility of continued discipline for Lynch, and on the larger importance of players communicating with media.)

“When he gets fined,” says Mayne, “I think he says, ‘Whatever, I’ll just shoot another plumbing commercial to pay for it.’ ”

For a time, it was refreshing that Carroll had removed all expectations of Lynch beyond being a good teammate, producing on the field and staying true to himself. But then Lynch appeared to have violated one of the three rules, getting arrested in California in July 2012 for alleged drunk driving. (He pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of reckless driving in February 2014.) More recently, it seems that workplace politics have allowed dissonance to creep in, as media leaks have hijacked Lynch’s narrative.

He held out for more money this offseason, and returned after the team capitulated several bonuses but reportedly fell $5 million short of Lynch’s asking price. Amid reports that Seattle had “grown tired of his ways” and considered trading him this season, Silver asked Lynch in November if he thought he’d be a Seahawk in 2015. His answer was vaguely accusatory and positively annoyed.

“Do I think I’ll be gone after this season?” Lynch said, via NFL.com. “I don’t know, man. The Seahawks, their front office gets in the media; they talk a lot. I don’t talk too much. I just play the game.

“If they have something going on, I don’t know about it.”

Then came Ian Rapoport’s report that Lynch is considering retirement after the season. “One issue for Lynch,” wrote Rapoport, “is health-related. He’s missed just one game in the last four years, but he has battled back pain throughout. Thanks to countless hits over the course of his career, the cartilage in his spinal cord is compressed, which brings him discomfort.”

His closest friends support the notion Lynch could soon call it a career.

“We all know how long he’s been dealing with his back,” Washington says. “He wants to leave an impact after football and he doesn’t want to be crippled later on in his life. He loves the game, it’s more about physical health.”

If Lynch were to call it quits, or even take a victory lap in another city, he’ll leave a legacy as one of the most powerful running backs in the game’s long history. Even in Sunday’s statistically ho-hum performance in Philadelphia, he was dominant in bursts, stiff-arming 310-pound Eagles defensive tackle Bennie Logan to the ground during a third-quarter sprint and plowing through four tacklers—including friend and Cal alum MychalKendricks—on his way to a first down in the fourth. After that play and many others, Eagles defenders said, Lynch got up giggling.

“He just runs like he’s mad every play,” says Eagles safety Nate Allen, “but when he gets up, he’s laughing and joking about stuff with his guys, our guys.

“Not like taunting. Like he’s out there having the time of his life.”

In the locker room after the game, Lynch grabbed Sherman and hollered in his face as if they were out on the practice field, not surrounded by curious eyes and ears in the basement of The Linc. He once told Sherman early in his career, in not so many words, to never let the judgments of other people dictate your actions.

“It was some of the best advice I’ve ever had, but he didn’t say it like that,” Sherman says. “He said it in a ‘Marshawn kind of way’.”

When I approached Lynch moments later, I held a notebook that contained a short list of questions I hoped to ask if he would agree to an interview.

What will you miss the most about this game when it’s over?

What coach had the greatest impact on you?

Would you be satisfied with your career if it ended tomorrow?

But I never got that far.

He looked at me in that ‘Marshawn kind of way’ and shook my hand.

“All I have to say is, Yes, Lawd.” Then he walked away.